| The Mighty Penn with a Contrived Imperialist Heart |

|

| Written by Piroska Csúri |

|

Response to Filler, Martin (2009) "The Mighty Penn," New York Review of Books, 19 October, 2009.

In our vigourously and light-heartedly postmodern, reception-idolizing present authorial intentions might not be considered the definitive last word as regards to the interpretation of an image. Nevertheless, while ignoring or by-passing non-visual sources such as the image-makers own texts that might provide a clue as for those original intentions can easily lead to eminently poetic-sounding interpretations, they turn out to be completely arbitrary, boundlessly subjective, and academically unsustainable. This way of proceding with interpretation of visual materials thus constitutes a mighty dangerous trap. In anointing Irving Penn´s Cuzco children (1948) an unsurpassable masterpiece portrait and "irrefutable proof positive" that Penn "had a heart" ("The Mighty Penn," NYR, November 19, 2009, p.21), Martin Filler seems caught tightly in just that trap.

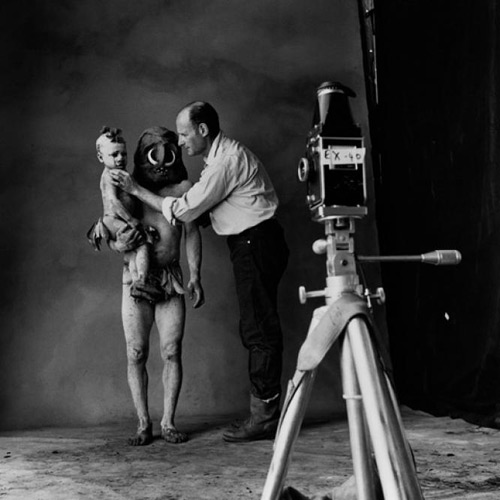

On his magazine assignments to "exotic" destinations (be it New Guinea, Cameroon, Morocco, the Republic of the Dahomey, or Peru) fashion photographer Irving Penn often moonlighted as a deep-feeling amateur (or dilettant?) artist-ethnographer. On these escapades, he set out to realize his youthful dream of photographing "disappearing aboriginees in remote parts of the earth". Images from these trips were finally compiled in his 1974 book Worlds in a Small Room.1 In his prologue to the book, Penn exults that, to his surprize and to his heart´s content, "[t]aking people away form their natural circumstances and putting them into the studio in front of a camera did not simply isolate them, it transformed them. [...] As they crossed the threshold of the studio, they left behind some of the manners of their community, taking on a seriousness of self-presentation that would not have been expected of simple people. [...] they rose to the experience of being looked at by a stranger." A stranger, a rather particular, peculiar stranger.

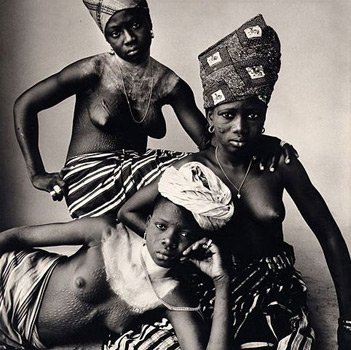

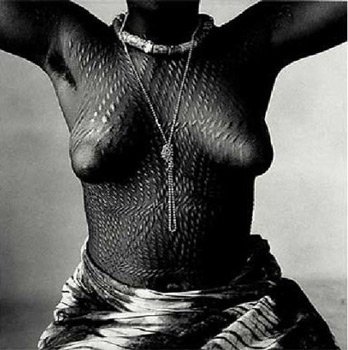

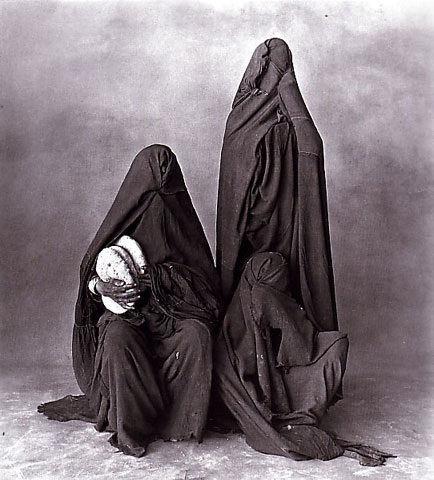

Quite contrary to Filler´s claims,2 in looking at them as the imperialist-minded stranger, Penn cast a hopelessly contrived and absurdly condescending eye on his subjects. To his eyes, Dahomey young girls "...were mermaids swimming around our boats, more at home in the water than we were on top of it." While in New Guinea, he "couldn´t speak to [his] subjects even in pidgin, but [he] was able to select them and then to pose them by touching their cool bodies and pressing them gently into various poses and relationships that seemed true for them." The south of Morocco, "a mysterious world of casbahs, oases, horsemen, and painted women" had such a magnetism on him that he dreamed of going back there in order "...to penetrate more deeply this Islamic fairyland and record the look just of the people themselves."

It was on his 1948 Vogue assignment to Lima, Peru that Penn decided to "spend Christmas in Cuzco, the town that I had heard about and had a hunch about." "...[S]ending the propietor away to spend Christmas with his family", he rented a daylight studio ("a Victorian leftover") in the center of the town3, and set to task. "When subjects arrived to be photographed they found me instead of [the proprietor]. Instead of them paying me, I paid them for posing, a very confusing affair." Very confusing indeed, but for whom?

Through his gaze, a hotchpotch of rancid imperialism4, arrogant sense of superiority, pastoral-oozing nostalgia and disquieting spectatorial posture, --instead of creating a 20th century masterpiece-- Penn transformed the take of the Cuzco children into a bitter parody of a 19th century provincial studio portrait bordering a cruel and perverse spectacle of the Other.5 Standing barefoot, in picturesquely ragged clothes, posed contra natura as a disturbingly premature couple, the children´s image gravitates inevitably towards the stubbornly evergreen genre of the studies of freaks of all kinds, unwilling subjects to an ancient and practically ineradicable voyeuristic passion.6 Cuzco children hence falls neatly in the tradition of a spectacularization of the "deviant" Other, a practically unresistable urge so perfectly embodied by people lining up to take an excited peep at the bearded woman, the Siamese twins, the elephant man or other human deformities at the travelling country fair.7

"From the very first glimpse the look of the inhabitants enchanted me—small, tight little ¾-scale people, wandering aimlessly and slowly in the streets of the town." - Penn wrote. "Cuzco is the center of the ancient Inca civilization, but it is difficult to imagine the present inhabitants as descendents of the brilliant engineers of the Inca cities and temples. Could their torpor be the effect of the coca leaves they chew all day?" Straight from the horse´s mouth. That is the mighty, masterpiece-snapping Penn speaking eloquently from his heart. But is there anyone listening? What kind of a heart is that?

Piroska Csúri

** 1. The book was published by Grossman in New York. All quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from Penn´s texts accompanying this edition. (back) 2. "...Penn treats his solemn-faced subjects with as much resepct and dignity as Mathew Brady did when he inmortalized Abraham Lincoln, and the same tenderness and affection with which Velázquez portrayed the Spanish infanta and her mastiff in Las meninas." Filler, p.21. (back) 3. The studio in question happened to be that of Martin Chambi (1891-1973), native Peruvian photographer. Internationally prized Pictoralist of his time, now renowned world-wide as possibly the first indigenous photographer in South America, his name was nevertheless completely erased from the international photography consciousness up until being (re)discovered by photogpraher and anthropologist Edward Ranney in the mid-1970s. (back) 4. "The Indians seem surprizingly Mongolian in facial construction.", op.cit. (back) 5. By pure coincidence. Jonathan Raban´s "American Pastoral" in the same issue of the NYR (October 19, 2009, pp.12-17) provides other examples of such a "beautifying" transformation of the poor by the gaze of the rich.. (back) 6. On the other hand, Penn´s images of defiantly bare-breasted Dahomey women squeezed into a rigid piramidal composition (without doubt, a way of "taking [them] away from their natural circumstanes"), have some resonances of 19 century semi-antropological photographs that circulated as a form of soft porn of the period. (back) 7. Walker Evans, among others, provides images of such fairs vigourously surviving in post-WWII U.S. (back)

|