Galleries

Results 176 - 200 of 1334

|

|

|

Author:Pedro Meyer

It seems that nowadays there are more cancelled prizes, declared as void, etcetera, than awarded. And it always revolves around the manipulation issue.

This time it goes like this:

Luis Valtueña's contest first prize revoked because of the manipulation made to one of the photographs.

Editorial Department. Médicos del Mundo (Doctors of the World) has finally decided to declare null and void the first place given to the Italian photographer Francesco Cocco for his article about Afghanistan, awarded in the thirteenth edition of the Humanitarian Photography International Award Luis Valtueña.

Through a rather plain press release, the jury mentions the non-fulfillment of the award’s rules –specifically point 4, which refers to photograph alteration- as an argument to revoke the award.

In spite there are no more details given, weeks ago one of the photographs in this article, -one where several women covered by a “burka” can be seen-, was being questioned. The first suspicions arose when some observers, alien to the contest organization, stated that the image seemed to have been manipulated, in particular to clone one of the women.

Curiously, this same work by Cocco has been awarded this year at China International Press Photo Contest.

Doctors of the World has also informed about its decision declaring the first prize null and void, and cancelling the grant that was given to the photographer in order to develop a project in collaboration with this non governmental organization.

More information about this news:

Jury's press release

The question that appeals to us is if we are ever going to realize this is a lost battle, because of the simple reason that the juries do not have either good or solid arguments to stand up to their decisions.

I keep on thinking about the war against drug traffic taking place here in México. It’s the same idea. Instead of taking in consideration that drug problem is not solved by prohibiting them, but by rehabilitation and education. The image manipulation issue should be perfectly acceptable, under certain circumstances. But those circumstances are the ones the organizers of these contests, do not dare to define.

In this award winning photo’s case, I consider irrelevant that it was manipulated, more important is that I think it is a bad photo. And if the jury didn’t realize about the rough manipulation, meaning: bad image quality, then, those who we have to question are the members of the jury and not the photographer.

Wednesday, 21 April 2010

|

|

Author:Erick Schonfeld

Legend has it that when Cortes landed in Mexico in the 1500s, he ordered his men to burn the ships that had brought them there to remove the possibility of doing anything other than going forward into the unknown. Marc Andreessen has the same advice for old media companies: “Burn the boats.”

Yesterday, Andreessen was in New York City and we met up. We got to talking about how media companies are handling the digital disruption of the Internet when he brought up the Cortes analogy. In particular, he was talking about print media such as newspapers and magazines, and his longstanding recommendation that they should shut down their print editions and embrace the Web wholeheartedly. “You gotta burn the boats,” he told me, “you gotta commit.” His point is that if traditional media companies don’t burn their own boats, somebody else will.

Andreessen once famously put the New York Times on deathwatch for its stubborn insistence on trying to save and prolong its legacy print business. With all the recent excitement in media quarters recently over Apple’s upcoming iPad and other tablet computers, and their potential to create a market for paid digital versions and subscriptions of newspapers and magazines, I wondered if Andreessen still felt the same way. Does he think the iPad will change anything?

Andreessen asked me if TechCrunch is working on an iPad app or planning on putting up a paywall. I gave him a blank stare. He laughed and noted that none of the newer Web publications (he’s an investor in the Business Insider) are either. “All the new companies are not spending a nanosecond on the iPad or thinking of ways to charge for content. The older companies, that is all they are thinking about.”

But people pay for apps. Wouldn’t he pay for a beautiful touchscreen version of a magazine? Maybe, if it were something genuinely new that blew him away. It would have to be more than an article with video and graphics though. (I agree, otherwise it’s no better than a CD-ROM).

Oh, and he points out, that the iPad will have a “fantastic browser.” No matter how many iPads the Apple sells, the Web will always be the bigger market. “There are 2 billion people on the Web,” he says. “The iPad will be a huge success if it sells 5 million units.”

Despite trying time and again, Andreessen’s observation is that media companies have no aptitude for technology, nor do they really understand what technology companies do. The one thing technology companies do really well is deal with constant disruption. “Microsoft is going through this right now,” he points out, “Ballmer is not complaining about it.” He’s tackling it head on. So did Intel when Andy Grove gutted it to shift from memory chips to microprocessors. So does every technology company CEO. It is ingrained in the industry Andreessen comes from, so it is just obvious to him: “You are cruising along, and then technology changes. You have to adapt.” Media companies need to learn that lesson fast. To the extent that their products are now delivered and consumed as digital bits, they too are becoming technology companies.

Beyond the iPad, he believes that all the talk once again from big media companies about erecting paywalls or somehow charging for news, articles and video online is shortsighted at best. He comes back to the simple fact that the open Web is where the users are. Talking about paywalls and paid apps is like saying, “We know where the market is and we are not going to go there.” Print newspapers and magazines will never get there, he argues, until they burn the boats and shut down their print operations. Yes, there are still a lot of people and money in those boats—billions of dollars in revenue in some cases. “At risk is 80% of revenues and headcount,” Andreessen acknowledges, “but shift happens.” You’d have to be crazy to burn the boats. Crazy like Cortes.

by Erick Schonfeld

Thursday, 15 April 2010

|

|

Author:Michael Wolff

Everyone’s betting on the Internet’s next big thing. The author provides a tip sheet on competing theories–it’s the platform (Google, Facebook); it’s the machine (iWhatever); it’s digital behavior (Twitter); it’s porn (Skype sex!); etc.–along with his own hunch about the year to come. Plus: Live chat with author Michael Wolff about the Internet’s next big thing.

I am told so many things about what is going to happen in the Internet business—happen imminently, happen in a way to transform human behavior and aspirations, happen in a way to disrupt the powers that be, or to restore the powers that used to be—that I should be in a position, if I could just focus my attention, to get rich, finally.

Everybody I know who follows the next big thing believes that this year—emerging from recession, with the death of so many aspects of conventional media—will be a year of, in Internet-speak, radical inflection, precipitating a wave of acquisitions and I.P.O.’s and a river of new investment. If you can only focus on what so many geniuses are saying, you can win big. But deciphering the chatter is no small talent, because the technology business is at least as much talk as it is science. The next big thing can sometimes feel like the coming of Christ, but it can also feel like the internecine debates about socialist doctrine that famously took place in the cafeterias of City College, in New York, in the 1930s.

So what I am going to do here—rather in an effort to create a Next Big Thing for Dummies—is to try to align the factions, parse the theories, distinguish the geek Lenins from the geek Trotskys, and offer the possibility for you to profitably know what this year is going to bring (or, anyway, hold your own at a cocktail party).

Actually, start with a Russian. Yuri Milner is a 48-year-old Muscovite, billionaire, and Putin look-alike, who, in the past year, has become one of the largest investors in digital media in the U.S., elevating the next big thing to something like geopolitical status. Other Russian billionaires buy sports teams or newspapers; Milner is buying “platforms.”

Milner is the biggest outside investor in Facebook, and in December he bought a large stake in Zynga, the fast-growing online-game company, whose games—FarmVille, Café World, and Mafia Wars—are played mostly through Facebook.

He says he’s betting on personalities—Mark Zuckerberg, the C.E.O. of Facebook, and Mark Pincus, who heads Zynga—which is something investors often say: it’s all about talent and drive. But a platform bet suggests a view beyond just gifted management. It’s a control-the-universe play.

Having a platform, in this geopolitical theory, makes you a superpower. Microsoft achieved world domination with Windows when operating systems were the ultimate platforms. But a platform is now a more metaphorical construct, suggesting not just functionality but a framework of behavior, and even a point of view, that habituates users and fosters their dependence, with an eye toward subsuming the rest of the digital world. Like Google.

And, in Milner’s view, like Facebook.

Or, in Steve Jobs’s view, the iPhone—another stab at his dream of controlling both the hardware and the software that control the world.

The platform theory of global conquest holds that Internet dominance has, other than for Google, been elusive, in part because of constant shifts in technology. But the Internet, after 15 years, has, in the platform-supremacy perspective, come to a level of maturity. “The Net is now just another utility, like electricity, water, etc.,” says Mark Cuban, who made one of the biggest personal fortunes of the dot-com boom when he and his partner, Todd Wagner, sold Broadcast.com to Yahoo for $6 billion, in 1999.

In other words, if you can become a ubiquitous, octopus-like, hydra-headed, chameleon-ish, integrated horizontal and vertical database and command center, it could be years before a new technology challenges your dominance.

Which is why the emergence of another platform is so compelling.

Facebook’s move at the end of last year to revise its privacy settings, an illusory offer of more control to the user, was really part of an ongoing attempt to make more user data public, shareable, and searchable—meaning Facebook has the opportunity to become the platform through which we search, not just public information but individual information, ever growing masses of it (including pictures). Search moves from the Web into people’s lives.

This prospect leads, in just about everybody’s estimation, to an I.P.O. for Facebook this year, which in its size and giddiness will transform the industry with new liquidity and provoke the ultimate superpower platform war, a face-off between Google’s dominance over Web-page-based search and Facebook’s command of the “social graph.”

And yet, such platform politics, such continuing belief in the possibility of control, may be just so Cold War. The better way to look at what changes the game, according to a group you might call the digital behaviorists—part hucksters and part self-appointed sociologists—is to understand how the Internet radically alters the desires and habits and actions and reactions of the people who use it.

Clay Shirky, for instance, the author of Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations, is a man whose name is now uttered in technology circles with the kind of reverence with which left-wingers used to say, “Herbert Marcuse.” “Web 3.0 is not an upgrade—it’s a revolution,” says Shirky characteristically. Shirky, along with Jeff Jarvis, a Cotton Mather (or Billy Sunday) figure, who has turned his sky-is-falling lectures to old-media executives into a lucrative consulting practice to old-media businesses, Chris Anderson, Wired’s editor in chief, and Jay Rosen, an N.Y.U. professor—all dedicated bloggers and, in Internet parlance, “quote monkeys”—have essentially morphed the anarchic, 60s-style, Whole Earth Catalog roots of the Internet into aggressive business theory.

At its heart, the digital-behavior theory is that the old media business imposed an unnatural behavior on its users—not least of all a strict divide between creators and audience. The Internet, with a flat hierarchy, cheap distribution, and virtually no production barriers, lets people express themselves more naturally. We’re collaborative animals, it turns out, and joyful amateurs, interested more in entertaining and informing ourselves than in being entertained and informed by professionals.

Shirky’s research actually concludes that people like to work for free, and that they are more productive when they do so, which, if you think about it, challenges all economic theory, but, if you think about it some more, just says people like their hobbies and are particularly proud of having an autodidactic expertise.

So what happens when you harness all the world’s hobbyists and autodidacts into a new business model?

Digg, for one, wherein users select and rank news, which, without one editorial employee, has more than 40 million users, making it one of the biggest news sites on the Internet, producing a version of news that no professional would ever create.

Or “Charlie Bit My Finger,” wherein a British toddler bites his deadpan brother’s finger to great merriment, which, with 149 million views on YouTube, is bigger than the Super Bowl.

And if this obsessive disgorging and contributing produces, as Jarvis acknowledges, “a mountain of crap,” this just means the next big thing will be about sorting, sifting, and filtering the crap.

Even the need for filters and editors, in the behaviorists’ scheme, will be met by a product of the new behavior: Twitter.

Twitter, according to the behaviorists, is both the finest expression of free labor and infinite disgorgement, and the way we will navigate through ever greater vapidness and clutter. Twitter is, for the behaviorists, a second-by-second, real-time database of the human experience, a searchable record of all thoughts and actions, which will generate, according to Biz Stone, its co-founder, a billion search queries a day in the coming year. Instead of Google algorithms establishing the information hierarchy, the mass of Twitter-centric humanity—or one’s pre-selected peer group among Twitter-centric humanity—will establish what’s important and hence what comes up first in search results. “E-mail and I.M. have morphed quite naturally into a much broader and more open public discourse,” says Stone, a discourse which in itself becomes a primary navigation tool and a way, “well beyond entering a term in a box and clicking a button,” of interacting with the information world.

The live Internet, in the behaviorists’ eyes, is the next big thing. Web sites and Web pages are out of date. “Google,” says John Borthwick, whose Betaworks is a venture-capital firm that invests solely in behaviorist business models, “still thinks of the world as pages.” In Jarvis’s declaration, “media is no longer a product.” It is not a production. It is not a box-office hit. It is how we contribute to and how we benefit from our collective expressiveness.

Which, according to various done-it-and-seen-it-all types, is a lot of hooey. Or, to the extent it’s true that the costs of production have gone down and the available labor market has increased, it’s all about a cost-savings opportunity.

Michael Wolff

Thursday, 15 April 2010

|

|

Author:Alejandro Malo

There is an apparent contradiction amongst the documentary and artistic value of an art work. On one side, a photographic document aspires to be an instant’s testimony —or a series of instants in the case of an essay— with a location, characters and precise elements, that lead to an exact interpretation; and, on the other side it is accepted without further questioning that any work of art, mostly in the photographic field subsequent to twentieth century’s vanguards, must allow diverse interpretations that avoid it to be run down as a mere illustration or sample of technical mastery. If, besides what was previously said, we emphasize the distinction made by uncountable contests, as something almost obvious, among photojournalism and artistic photography, almost any attempt to conciliate both expressions seems destined to failure.

But there happen to be exhibitions where —in spaces destined to art— works resulting from a documentary task are praised. It would be enough to mention as examples, the multiple exhibits, in several continents, of Rober Capa’s work, Gerda Taro’s or Josef Koudelka’s; but more recent works can be highlighted, as the series belonging to Chien Chi-Chang, those of Manuel Rivera-Ortiz or the large-scale ones by Luc Delahaye. And it’s also worthwhile to point out that, in certain cases, due to time passing by, geographic remoteness or simply lack of context, a documental image transforms into a vaster image, where any war represents the violence and anguish of every war, hunger portrayed on a face gathers the forcefulness of all the famines, and a desolate sadness becomes each and every imaginable grief.

Is in this space where —a little like what Alejo Carpentier, Julio Cortázar and many other Magic Realism members did in literature— it is achieved that a precise expression manages, without leaving its particularity aside, to present universal concerns; and it is there where a document, without loosing a bit of accuracy, offers interpretations that are renewed with every look. But it is also fair by the searching of these spaces that we convene to a dialogue about the legitimate aspiration of any photodocumentalist to lay out a bridge towards art, and to reflect without prejudices on the possibilities of a shared territory.

Alejandro Malo

Thursday, 08 April 2010

|

|

Author:Hans Durrer

Review of: David Friend (2007), Watching the world change. The stories behind the images of 9/11. New York: Picador (464 pages; ISBN: 978-0312426767)

The World Trade Center disaster at that fatal date of September 11th, 2001, probably was the most photographed event of our time. A number of those photo's now have been collected in a book by David Friend who added his insightful comments. Hans Durrer reviews and reflects on the results.

Disasters in the age of digital photography

Like probably quite some others, I feel somewhat overfed when it comes to 9/11. So why then would I read yet another text about it? Well, I'm interested in photographs, and in photojournalism, and especially in the stories behind the photographs, and when I came across reviews of David Friend's "Watching the World Change" I became curious and remained so page after page of this truly fascinating work.

The author, David Friend, formerly Life's director of photography, is Vanity Fair's editor of creative development. Moreover, he is a good writer, a tireless journalist, and, very probably, a workaholic — the research alone that went into this book is immense and impressive.

Remember the image of George W. Bush at Ground Zero? The one where "... he stood in a windbreaker on the smoking heap at Ground Zero, flag pin on his lapel and bullhorn in his mitt. He embraced Bob Beckwith, a sixty-nine-year old firefighter from Queens ..."? One of Bush's longtime media advisors opined that this image "will be the most lasting and iconic image of [his] presidency," the editor in chief of the New York Daily News believed this scene to be unscripted, a strategist, who worked on John Kerry's campaign, thought it calculated, and Luc Sante, the culture critic and photo historian, also believed it to be scripted for "with Bush you never get a moment that is not stage-managed."

"Compelling ... Surely the most original treatment so far of the cultural impact of the day," Frank Rich of the New York Times is quoted on the back cover and, yes, that is most probably true, but, what's more, this is absolutely singular journalism (well-told, detailed, and with a keen sense for narrative flow) that not only demonstrates how we — by taking, looking at, distributing, and sharing pictures — are trying to give significance to what surrounds us but also proves that it is not the (dramatically structured and enhanced) story that makes good journalism but the accurate and sympathetic rendering of how people deal with what happens.

9/11 was probably the most photographed event of our time. This is one of the impressions that you get when spending time with this book. I know, we live in a world of pictures, yet it would have never occurred to me that so many people took pictures — videos and stills — on that day. "A French documentary filmmaker, a Czech immigrant, and a German artist — New Yorkers all — each happened to have cameras rolling and focused on the World Trade Center when it was attacked. Moments later, artist Lawrence Heller, who had heard the first jet slam into Tower One (the north tower), picked up his digital video camera ... People photographed from windows and parapets and landings. They photographed as they fled: in cars, across bridges, up avenues blanketed in drifts of ash and dust. They even photographed the images on their television sets as they watched the world changing, right there on the screen." And there was, for example, Patricia McDonough, a professional photographer, who, after taking quite some pics that would later appear in Esquire and other magazines, thought that photography "suddenly seemed superfluous," loaded her bike bag with disposable gloves and water bottles — "I had a lot of Red Cross training, CPR classes, I have preternatural calm in disasters" — and rushed to help.

Holding back on publication

"Astoundingly," Friend comments, "dozens of photographers continued to shoot even as they sensed that their own lives were at risk — when clouds of debris, from the falling towers, mushroomed up and down the streets." But what did people compel to take photographs in such a situation? Sure, answers may vary but quite some people probably "had to photograph it and then look at it in order to validate that it actually happened," as curator and writer Michael Shulan opines. Yet despite the many pictures that were shot on 9/11 and the following days (by TV-cameras, tourists, workers, passersby), it was by no means easy for professional photographers to go about their work. Christopher Morris, for instance, says: "I got on the scene, got past the barricades, and was immediately seized upon by the police. It was impossible to shoot. Everybody hated photographers. We were like pariahs."

One of the reasons that so many pictures were taken on that day is that it was possible: 50% of Americans live in homes with a digital camera; up to 2006, 50 million working cell phones in the US had cameras in them, I learned. David Friend thinks that the week of 9/11 was the beginning of the digital age, part of which is digital newsgathering. In the words of Nigel Pritchard of CNN: "You were no longer tied to a piece of cable and a satellite truck. We could go anywhere and broadcast with a battery pack." Modern technology (digital cameras, phone lines, fiber-optic cables, the internet, satellites) has made it possible that "in a matter of minutes, everyone with a monitor, almost anywhere in the world, was able to access similar footage shot only moments before," as Friend explains.

In the days following 9/11, there were hardly any pictures published (in the US) that showed body parts, blood covered survivors or people jumping from the windows of the World Trade Center. This self-censorship, as Friend elaborates, might have occurred because "editors, to some degree, might have felt protective of their own, beholden to people they considered members of nothing less than an extended family — vast, grieving, and interconnected (...) In short, they just couldn't bear to have anyone see them this way." Another reason surely was, as Time's director of photography, Michele Stephenson, says, that "there was not a lot left of them."

But what about photos of jumpers, why didn't we get to see these? Joe Scurto, for instance, saw "at least a hundred people jumping. The were coming down like rain." Well, there is one that has come to be known as The Falling Man, taken by veteran Associated Press photographer Richard Drew; "the most famous picture nobody's ever seen," as Drew says. As Friend sees it: "Nowadays ... news organizations tend to play it safe, having been subsumed by media conglomerates that give less credence to exposing harsh realities than to turning a profit, entertaining mass audiences, and satisfying skittish advertisers."

A personal book

There are also bizarre things to be learnt from this great book, for instance, that the Stars and Stripes flag that the firemen raised at Ground Zero has disappeared. Or the story of an ad agency copywriter and a photographer who were flipping through Time magazine (the cover photo was shot by the photographer), when a man came running towards them, grabbed the magazine and, landing on a double-page spread, announced that these were his images. And, when the ad guy pointed out that his friend had shot the cover, said: "Ahh, you're the one who beat me out of the cover."

Not bizarre at all, but very interesting (and wonderfully instructive) I've found this: After the attacks on the Twin Towers, all commercial flights across American airspace had been immediately suspended. All of a sudden, the air was clear of contrails (thin stripes of condensation the many jets that cross the continent leave behind) and visual and meterological data produced over the three days the planes were grounded indicated "that North America's temperature swing (the range between the average daytime high and the average nighttime low) widened by an appreciable three to five degrees Fahrenheit ... this suggested ... that contrails, over the years, have tended to tamp down temperatures (a phenomenon called global dimming), possibly hiding what could be even more severe ramifications of global warming."

Above all, this tome impressively demonstrates what it means to live in a world dominated by pictures. Friend writes: "Most of us hardly realize how pictures serve as a nourishing undergrowth in the recesses of our lives. The weather forecast that helped me choose what I would wear today was created by meteorologists interpreting sequences of still photographs. The security cameras in my office building, my local bank, the various public spaces I traverse each day, are recording me in a steady stream of surveillance shots. My computer stores images and exchanges them with other electronic devices. My cellular picture phone ..."

Finally, taking pictures and looking at pictures is personal. And thankfully, this is a personal book. Not in the sense that David Friend is pouring out his soul but in the sense that he tells you how he goes about his work: "I phoned a friend in London to see how he was coping, to offer support ... On September 11, my friend, an executive at eSpeed [a Cantor subsidiary in London] hand been on a conference call with his counterparts on the 103rd floor of Tower One. Over the course of his call, he had listened to what he remembers as the 'turmoil over the squawk box,' as colleagues spoke about some sort of explosion. Later came sounds that he now claims are too nightmarish to describe."

In the same vein he writes about how his then thirteen-year-old daughter Molly reacted to the news that John Doherty, the father of her friend Maureen, had not returned from the World Trade Center: "Over the week that followed, Molly would periodically go to the dining room sideboard, open the left-hand drawer, and take out a framed photo she kept there of nineteen sixth-grade girls from the Ursuline School, including Maureen and Molly, posing in their finest dresses." And about how he himself attempted to come to grips with post 9/11 reality: "I stared at the framed photo beside the prayer book. It showed my sister, Janet, brown eyes twinkling, her young life gone in a single stroke, in a car crash, in 1997. Yet I felt through the photograph that her absence was somehow a presence, and that she must be busy. This nurse, who used to work on a children's bone marrow yard in Seattle, would have been swamped that week. Watching her smile on the nightstand, I thought Janet must be ministering and offering guidance and compassion, now that heaven was packed."

2009 © Hans Durrer / Soundscapes

Thursday, 08 April 2010

|

|

Author:ZoneZero

Reality is no longer what it used to be and for some time now, it has ceased to be the way it is portrayed. Throughout the last century, the belief that matter and reality shared a precise correspondence crumbled as it was attacked on various fronts. First physics put us face to face with the relativity of time and space, then the social sciences showed us that language determines the way we construct our perception of the world, and in the final decades, technology has been enveloping us in spheres where virtuality in many ways seems to be more immediate and in different senses more real than the material presence of that same entity that is represented. An example of this is the friend on the other side of the world with whom we can speak through a social network or a videoconference, and it seems much more real than our neighbor, with whom we will probably never exchange even a good morning.

Alejandro Malo

Read More...

Galleries

From our Archive

We Recommend

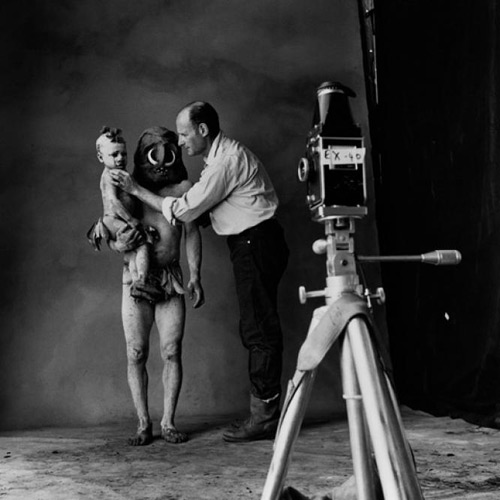

Maggie Taylor & Jerry Uelsmann podcast

Tom Chambers | Diseñador y Fotógrafo

CM Top 50: Tom Chambers

Photography Undergoes a Sex Change:the art of Tom Chambers

Maleonn

Postman's letter, by Maleonn

Maleonn

Maleonn

Tuesday, 06 April 2010

|

|

Author:Media Helping Media

31 March 2010

Government lawyers confirmed to the Vacation Bench of the High Court today that the police deployed in front of the DRIK Gallery had been withdrawn and that there would be no obstruction to the exhibition from now on.

Dr. Alam’s lawyer submitted that police had continued to block visitors even uptil 4:30 pm on 30 March and sought an assurance from the Government that there would be no further interference with visitors attending the Gallery.

Additional Attorney General MK Rahman referred to information received from the Dhaka Metropolitan Police Commissioner and the Ministry of Home Affairs, that there was no need for a police presence.

In view of these statement, the Court observed that it would not pass any order at this time but that if further obstruction to the exhibition took place before the re-opening of the High Court on 3rd April, the petitioner would be at liberty to seek necessary orders from the Vacation Bench.

Background:

The Vacation Bench of the High Court for the second day heard a writ petition challenging the continuing police action preventing the entry of viewers to the exhibition by Dr. Shahidul Alam at the DRIK Gallery entitled ‘Cross-fire”, which consists of interpretive photographs and an interactive google map which shows locations where the bodies of persons allegedly killed in ‘cross-fire’ by security forces were reportedly found.

Dr. Alam challenged the actions of the police, including Special Branch and RAB in directing him to close down the exhibition hours prior to its scheduled inauguration on 22nd March, and then the continuing police deployment in front of the DRIK Gallery in Dhanmondi from the afternoon of 22nd March onwards. As widely reported in the media, the police had prevented noted author Mahasweta Devi and other invited guests from entering the exhibition for the inauguration, and subsequently prevented other visitors to the exhibition from entering the premises. The police stated that DRIK needed ‘prior permission’ to hold the exhibition and that going ahead with it would ‘cause unrest’.

The writ was filed by Dr. Shahidul Alam, photojournalist and MD of DRIK. The respondents to the writ petition were the Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, the IG of Police, the DG of RAB, the Dhaka Metropolitan Police Commissioner and the Officer in Charge of Dhanmondi Police Station.

© Media Helping Media

Monday, 05 April 2010

|

|

Author:Rezaur Rahman

26th March morning at Drik. Conversation between young man and guard as narrated by guard.

Young man: Egulo ki? Egulo ki hochche ekhane

BD: What are these? Whats going on here?

Guard: egulo prodorshoni hochche ekhane

BD: It’s an exhibition going on here.

YM: ki nam etar kin am. Oi eta ki korse. Ki korse eguli. Korse ke. Ki nam tui bol tui bol.

BD: what’s its name? Oi, whats this? Whats all these? Who has done it? Whats the name, you tell me.

G: etar nam crossfire bhaiya. Apni janen na…

BD: It’s name is CROSSFIRE brother. Don’t you know…

YM: oi e korse ke, korse ke. Ke. Ke. Shohidul alom? Shohidul alom korse. Oi o thake kon jaigai.

BD: Oi, who has done that, who, who – Shohidul Alom? Shohidul Alam has done it. Where does he live?

G: bhaiya ami gate er security. Ami ki kore bolbo. She ki kore na kore. Kothai thake. Ami egulo kichu jani na bhaiya.

BD: Brother, I’m the gate security. How am I supposed to know these– what he does or doesn’t - where he lives? I don’t know anything brother.

YM: ei or ki morar bhoi nai? Or ki morar bhoi nai akdom i? ei or bou polapan nai? Meye chele meye nai? Ei bol nai nai?

BD: oi, doesn’t he fear of death? Doesn’t he fear of death at all? Oi, doesn’t he have a family? Doesn’t he have any children? Oi, tell me?

G: bhai apni ato uttejoto hochchen kano? Amar moton bhodro bhabe kotha bolben apni. Bhodro shore kotha bolben. Eta obhodror jaiga na. apni jebhabe kotha bolchen ebhabe kotha bola hochche na apnar.

BD: Brother, why are you getting so tensed? Talk to me in gentle manner as I’m doing. Talk to me in gentle tune. Its not a place for a indecent person. You can’t talk the way you’re talking.

YM: ei beshi bolish na.

BD: Oi, don’t talk too much.

G: kano? Ami ki beshi bollam? Apnar shathe ami ki bhabe kotha bolte chai ar apni amar shathe ki bhabe kotha bolchen?

BD: Why? Have I said a lot? How I am talking to you and how are you talking to me?

YM: tui bolish. Shohidul alom jokhon tokhon guli kheye morbe. Rastar upore tao

BD: You should tell – Shohidul Alom will dye any time by gun shot – on road too.

G: bhai apnar nam ta ki bolben please?

BD: Brother, will you tell me your name please?

YM: ei amar nam shune labh nai. Tobe mone rakhish. Mone rakhish bujhli?

BD: Oi, these are no need to know my name but do remember – remember, will you?

G: bhaiya please apnar nam ta bolen na bhaiya. Apni chole jachchen kano? Daran na bolen. Apnar nam ta ektu bolen. Apnar kotha ami bolbo take. Apnar nam ta bolen amake. Ami shamne bolbo.

BD: Brother, please let me know your name. Why are you leaving? Hold-on, tell me – tell me your name. I will let him know what you said. Tell me your name. I will tell in front…

YM: walks away:

G: bhaiya please apnar nam at bolen

BD: Brother please tell me your name

YM: tui bolish akta public ei kotha ta bolche.

BD: You tell him that a public told him that.

G: ji ami take bolbo

BD: yes, I will tell him that

27th March afternoon: transcription from video (conversation in presence of police, between YM and SA unrecognized by YM)

YM: amra dekhte ashchi crossfire ta lagaise ke. Shontrashi mortase amra shantite baicha asi. Ami shontrashir guli te morte raji na. shontrashi amader ain srinkhola bahinir hate moruk. Ami ta dekhte raji asi. Jara ei shob kortese (pointing to billboard of exhibition), tara hoitase shobche boro shontrashi. Tader crossfire e tader mora uchit.

BD: We came to see who put the crossfire on. Terrorists are dyeing and we are living in peace. I don’t want to dye of a shot from a terrorist. Terrorists should dye from our law enforcement guards. I am ready to see that. Those who are doing that (pointing to billboard of exhibition), are the biggest terrorists. They should dye from their own crossfire.

Police: jara lagaise?

BD: Those who created?

YM: jara ei shob babostha korse. Shontrashi mortase ami shantite baicha asi. Aram e asi. Ami chaina amar ma amar bon amar bap re shontrashi ra maira pheluk. Bonre dhoira nia jak. Ami eita chai na. shontrashi re amra palte chai na.

BD: Those who prepared all these. Terrorists are dyeing and I’m living in peace. Living in peace. I don’t want terrorists kill my mother, my sister, my father. Kidnap my sister. I don’t want that. We don’t want to raise terrorists.

Police: apni bolte chaitasen crossfire e jara mara gase tara prokrito shontrashi.

BD: You want to tell those who died in crossfire are real terrorists.

YM: akta duita to mortei pare. Desh hoitase ato tuk. Lok hoise sholo koti shotero koti. Dui akta to erokom hobei. Hobe na?

BD: One or two must have died. Country is just about that(small). Population is 160 million. One or two must become like that – won’t they be?

SA (without disclosing his identity): apni ki prodorshoni ta dekhechen bhaiya. Apni dekhechen?

BD: (without disclosing his identity):are you watching this exhibition brother? Are you watching?

YM: amar dekhar ichcha nai.

BD: I don’t wish to watch it.

ENDS

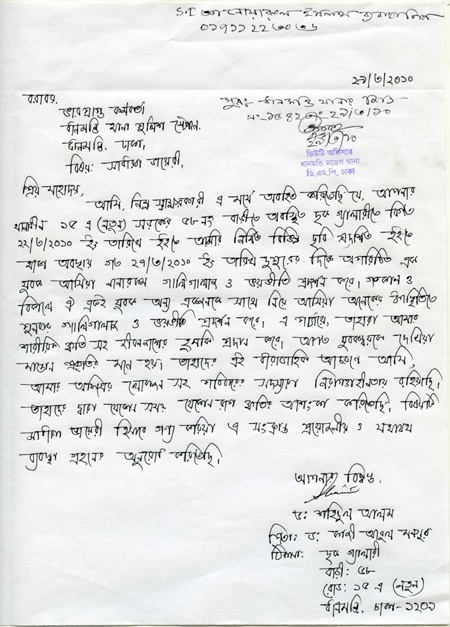

29th March 2010 Press Release

For Immediate Release

Photographer of 'Crossfire' exhibition threatened with ‘crossfire’.

A general diary (GD) was filed today by photographer Dr. Shahidul Alam at Dhanmondi Police Station, to register death threats placed upon the photographer.

Following the closure of the exhibition “Crossfire” depicting allegorical images depicting the extra judicial killings by the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) that have been going on since 2004, an unknown youth came to Drik premises in the morning of the 27th March 2010 and wanted to know who this Shahidul Alam was. Whether he had a wife and family. Whether he had children. “Is he not scared for his life? Does he not have any fear at all?” the young man asked the guard. He refused to give his name, but told the guard to tell Alam that “He will meet his death in the streets, by bullets. Don’t forget to tell him.” When asked again for his name he said, “Tell him I’m a member of the public.”

The following day the man returned in the afternoon along with another young man, and in the presence of a large number of people, including police, said “It is the person who organised this exhibition who should be crossfired.”

The GD was filed with S.I. Anwarul Islam. GD NO: 1542/29TH March 2010. Earlier in the day, Drik Picture Library Ltd. Filed a write petition (No: 2543/29th March 2010) against the government demanding that the blockade of the exhibition “Crossfire” be removed.

Contact:

A S M Rezaur Rahman General Manager Drik Picture Library Ltd.

Monday, 05 April 2010

|

|

Author:Shahidul Alam

22 March 2010 PRESS RELEASE

Drik Picture Library was forcibly closed down by the police today to prevent the launch of Pathshala, South Asian Media Academy, and the unveiling of a photography exhibition by photojournalist Dr Shahidul Alam, 'Crossfire.'

The Media Academy, an extension of Pathshala, South Asian Institute of Photography, regarded to be one of the best photojournalism schools in the world, intends to train other sectors of the media, namely broadcasting, print and multimedia journalism, and to build up a body of honest, courageous, energetic and skilled media professionals.

The exhibition, 'Crossfire,' curated by renowned Peruvian curator Jorge Villacorta, includes photographs and installations relating to the theme of crossfire and the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB).

From midday onwards, Drik was pressurised by RAB, police and Special Branch officials to close down the show on grounds that it does not have official permission, and later, on the grounds that it will create anarchy.

In the light of the lockout, the opening took place in a small impromptu programme held on the road outside Drik. The event was inaugurated by the celebrated Indian writer and human rights activist, Mahasweta Devi. Nurul Kabir, editor of New Age, M Hamid, CEO of RTV and Jorge Villacorta, curator from Peru were present, alongwith many artists and media professionals from abroad, and also, members of the public.

The forcible closure of Drik's premises is a blatant violation of our constitutional rights. Drik has organised hundreds of exhibition, and as is apparent by this closure, the government has invoked a prohibitive clause only because state repression was being exposed. It was police intervention which created disorder, not the other way round.

In its 20 years of existence, Drik has forged a unique position in the international cultural arena, which has earned Bangladesh a special place in the world of photography. The unfortunate event which was broadcast worldwide has tarnished the image of this democratically-elected government. We call upon the government to immediately remove the police encirclement, so that the exhibition can be opened for public viewing, and Bangladesh's image as an independent democratic nation can be reinstated.

Dr Shahidul Alam Managing Director

Monday, 05 April 2010

|

|

Author:Nadia Baram

Upcoming artist, Nicole Lesser, shares with us intimate portraits of her friends. Young, sensual, timid. The portraits are a delight.

To view more visit: http://www.nicolelesser.com/

Friday, 19 March 2010

|

|

Author:Pedro Meyer

World Press Photo has just disqualified Stepan Rudik from receiving the 3erd. prize story award in Sports Features.

Their argument goes that "after careful consultation with the jury, [it has] determined that it was necessary to disqualify Stepan Rudik, due to violation of the rules of the WPP contest". The photographer had removed a foot of one of it's subjects from a photo.

The photographer has explained that his motives behind the manipulation. "The Photograph submitted to the contest is a crop, and the retouched detail is the foot of a man which appears on the original photograph, but who is not a subject of the image submitted to the contest. There is no significant alteration nor has there been the removal of important information."

We fully support Stepan Rudik, and consider that the stance by World Press Photo, is yet one more instance of a jury not understanding the meaning of photography.

Let me reiterate for all those who have not given this subject too much thought. Photography by it's very nature is manipulation. Look at the contradictions, of this jury. That someone submits a crop of an image, seems to be quite acceptable. To remove a foot that is not part of the story, is worthy of being burned in a pire of ignominy. "How dare the photographer, have removed a foot", while cropping a picture was not an issue.

Apparently we still have a long way ahead of us, in teaching all these juries and organizations around press photography, that their moralistic stance, is tantamount to the Spanish inquisition, searching for sins that did not exist.

We at ZoneZero, stand fully behind Stepan Rudik.

Pedro Meyer

Friday, 12 March 2010

|

|

Author:Piroska Csúri

Response to Filler, Martin (2009) "The Mighty Penn," New York Review of Books, 19 October, 2009.

In our vigourously and light-heartedly postmodern, reception-idolizing present authorial intentions might not be considered the definitive last word as regards to the interpretation of an image. Nevertheless, while ignoring or by-passing non-visual sources such as the image-makers own texts that might provide a clue as for those original intentions can easily lead to eminently poetic-sounding interpretations, they turn out to be completely arbitrary, boundlessly subjective, and academically unsustainable. This way of proceding with interpretation of visual materials thus constitutes a mighty dangerous trap. In anointing Irving Penn´s Cuzco children (1948) an unsurpassable masterpiece portrait and "irrefutable proof positive" that Penn "had a heart" ("The Mighty Penn," NYR, November 19, 2009, p.21), Martin Filler seems caught tightly in just that trap.

On his magazine assignments to "exotic" destinations (be it New Guinea, Cameroon, Morocco, the Republic of the Dahomey, or Peru) fashion photographer Irving Penn often moonlighted as a deep-feeling amateur (or dilettant?) artist-ethnographer. On these escapades, he set out to realize his youthful dream of photographing "disappearing aboriginees in remote parts of the earth". Images from these trips were finally compiled in his 1974 book Worlds in a Small Room.1 In his prologue to the book, Penn exults that, to his surprize and to his heart´s content, "[t]aking people away form their natural circumstances and putting them into the studio in front of a camera did not simply isolate them, it transformed them. [...] As they crossed the threshold of the studio, they left behind some of the manners of their community, taking on a seriousness of self-presentation that would not have been expected of simple people. [...] they rose to the experience of being looked at by a stranger." A stranger, a rather particular, peculiar stranger.

Quite contrary to Filler´s claims,2 in looking at them as the imperialist-minded stranger, Penn cast a hopelessly contrived and absurdly condescending eye on his subjects. To his eyes, Dahomey young girls "...were mermaids swimming around our boats, more at home in the water than we were on top of it." While in New Guinea, he "couldn´t speak to [his] subjects even in pidgin, but [he] was able to select them and then to pose them by touching their cool bodies and pressing them gently into various poses and relationships that seemed true for them." The south of Morocco, "a mysterious world of casbahs, oases, horsemen, and painted women" had such a magnetism on him that he dreamed of going back there in order "...to penetrate more deeply this Islamic fairyland and record the look just of the people themselves."

It was on his 1948 Vogue assignment to Lima, Peru that Penn decided to "spend Christmas in Cuzco, the town that I had heard about and had a hunch about." "...[S]ending the propietor away to spend Christmas with his family", he rented a daylight studio ("a Victorian leftover") in the center of the town3, and set to task. "When subjects arrived to be photographed they found me instead of [the proprietor]. Instead of them paying me, I paid them for posing, a very confusing affair." Very confusing indeed, but for whom?

Through his gaze, a hotchpotch of rancid imperialism4, arrogant sense of superiority, pastoral-oozing nostalgia and disquieting spectatorial posture, --instead of creating a 20th century masterpiece-- Penn transformed the take of the Cuzco children into a bitter parody of a 19th century provincial studio portrait bordering a cruel and perverse spectacle of the Other.5 Standing barefoot, in picturesquely ragged clothes, posed contra natura as a disturbingly premature couple, the children´s image gravitates inevitably towards the stubbornly evergreen genre of the studies of freaks of all kinds, unwilling subjects to an ancient and practically ineradicable voyeuristic passion.6 Cuzco children hence falls neatly in the tradition of a spectacularization of the "deviant" Other, a practically unresistable urge so perfectly embodied by people lining up to take an excited peep at the bearded woman, the Siamese twins, the elephant man or other human deformities at the travelling country fair.7

"From the very first glimpse the look of the inhabitants enchanted me—small, tight little ¾-scale people, wandering aimlessly and slowly in the streets of the town." - Penn wrote. "Cuzco is the center of the ancient Inca civilization, but it is difficult to imagine the present inhabitants as descendents of the brilliant engineers of the Inca cities and temples. Could their torpor be the effect of the coca leaves they chew all day?" Straight from the horse´s mouth. That is the mighty, masterpiece-snapping Penn speaking eloquently from his heart. But is there anyone listening? What kind of a heart is that?

Piroska Csúri Buenos Aires, Argentina

**

1. The book was published by Grossman in New York. All quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from Penn´s texts accompanying this edition. (back)

2. "...Penn treats his solemn-faced subjects with as much resepct and dignity as Mathew Brady did when he inmortalized Abraham Lincoln, and the same tenderness and affection with which Velázquez portrayed the Spanish infanta and her mastiff in Las meninas." Filler, p.21. (back)

3. The studio in question happened to be that of Martin Chambi (1891-1973), native Peruvian photographer. Internationally prized Pictoralist of his time, now renowned world-wide as possibly the first indigenous photographer in South America, his name was nevertheless completely erased from the international photography consciousness up until being (re)discovered by photogpraher and anthropologist Edward Ranney in the mid-1970s. (back)

4. "The Indians seem surprizingly Mongolian in facial construction.", op.cit. (back)

5. By pure coincidence. Jonathan Raban´s "American Pastoral" in the same issue of the NYR (October 19, 2009, pp.12-17) provides other examples of such a "beautifying" transformation of the poor by the gaze of the rich.. (back)

6. On the other hand, Penn´s images of defiantly bare-breasted Dahomey women squeezed into a rigid piramidal composition (without doubt, a way of "taking [them] away from their natural circumstanes"), have some resonances of 19 century semi-antropological photographs that circulated as a form of soft porn of the period. (back)

7. Walker Evans, among others, provides images of such fairs vigourously surviving in post-WWII U.S. (back)

Wednesday, 24 February 2010

|