| Alternate Realities |

|

| Written by Alejandro Malo |

|

Reality is no longer what it used to be and for some time now, it has ceased to be the way it is portrayed. Throughout the last century, the belief that matter and reality shared a precise correspondence crumbled as it was attacked on various fronts. First physics put us face to face with the relativity of time and space, then the social sciences showed us that language determines the way we construct our perception of the world, and in the final decades, technology has been enveloping us in spheres where virtuality in many ways seems to be more immediate and in different senses more real than the material presence of that same entity that is represented. An example of this is the friend on the other side of the world with whom we can speak through a social network or a videoconference, and it seems much more real than our neighbor, with whom we will probably never exchange even a good morning.

However, although since the time of rock painting, human beings perceived and communicated reality more as something feared or desired, and not from a materiality that is always incomplete and illusive, photography continues to evoke the expectation of objectivity. At the same time it allows it to occupy a privileged place as a result of its verisimilitude, it subjects it to particularly harsh demands concerning its capacity for representation. But what happens when that same reality is constructed, just as nowadays, more as a territory of shared subjectivities? How can this everyday virtuality of ours be captured in images in which each evocation allows us to go back over the disturbing mysteries and surprises of childhood, each scene tells us some fantasy charged with symbols, but whose moral goes beyond us, and each corner opens doors to improbable, if not impossible, landscapes?

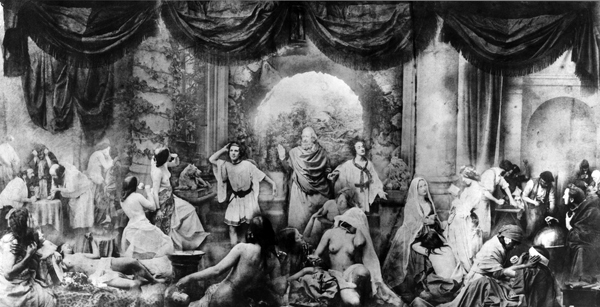

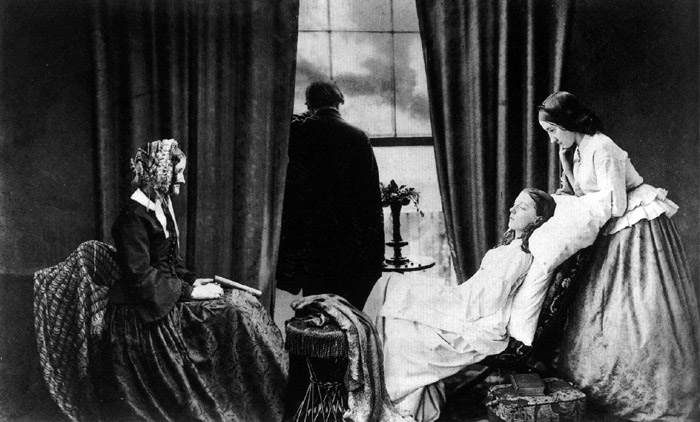

Almost since its origin, the language of photography has been served by highly diverse resources to allow for the representation of these particular corners. Since Óscar Gustav Rejlander constructed his allegory “The Two Ways of Life” (1857) with more than thirty negatives, Henry Peach Robinson presented his image of “Fading Away” (1858), also the result of multiple negatives, and several photographers developed the system suggested by Hippolyte Bayard (1852) of using negatives with different exposures for landscapes, photos ceased to be the testimonial result of what the lens had captured in front of the camera. If we add to this the exercises of staging that these same creators carried out and the work of women in the following decade such as Julia Margaret Cameron and Lady Clementina Hawarden, it is easy to understand this long tradition in which the image creates imagination and our everyday referents are mixed, thanks to each new technology, in illusive scenes, frame by frame, of some story, or where dreams assume an almost tangible materiality.

Just now, our daily life is saturated with “hard” data from all corners of the world, each time a tragedy shakes our monitors and at each moment when we are trapped between the vertigo of ongoing novelty and the immense magnitude of the happenings in the world. Just now, but perhaps as many times before, it becomes equally important to return our gaze to these alternate realities that open up a space of fantasy to us and invite us to imagine.

I don’t know, maybe I’m trying to convince myself that imagining together with others is a way of building a future for everyone. And also, why not, I like to think that this is an invitation to imagine, from the perspective of photography, a more dynamic, more open space that reinvents itself and that with enthusiasm extends itself, with new energy into this young century whose technology continues to make progress in leaps and bounds.

|