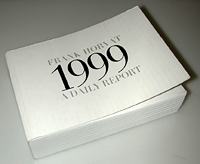

There is something about Daily Report, which draws me to return to it. A book as the title indicates of images taken each day during the last year of the millennium by French photographer Frank Horvat; a visual diary. It is not as though every image presented is memorable, or that the narrative flows with a determined conviction. This book has a quieter power. Perhaps what intrigues the viewer is precisely its considered mundane qualities, yet, it lacks banality. Horvat does not attempt to be monumental, there are no gimmicks or shocks. These are not epic images, yet they do reveal a great deal of information about certain specific worlds.

|

|

©

Frank Horvat

|

A modest book in many ways and yet Horvat’s visual diary is simultaneously a valuable undertaking. Beautifully printed, on high quality, heavy duty paper its form reflects a similar sensibility of precision and caring as the content. A simple idea, which could easily have been repetitive and uninteresting, but Horvat manages to maintain an energy, interest and rhythm that is sustained throughout the year. The book itself is compact, brick-like; it reminds me of one of those block calendars where you peel off each day which, as the year progresses becomes thinner and more manageable. Or a flip-book, which tells a narrative, but in this case there is no narrative, just a series of non-sequitur which when run together produce a sense of pleasant chaos. Like a Codex there is no necessity for a linear reading; there is ultimately no structure or revealing narrative that demands the calendar be observed. It is a book that can be returned to; images that can viewed one day at a time or the year in one sitting.

Horvat’s record of 1999 is a personal testimony without the pretensions of being any more than that. However, how reflective is this of his normal year? Funded in part by Kodak France and other corporations, the reader is left unclear about issues, which are significant to a reading of the overall content of the book. One cannot but speculate, how much did the funding of this project influence and change the structure of Horvat’s days during 1999? Did this funding “free-up” his time from other jobs in order that he concentrate on A Daily Report, or provide him with the financial support to travel for this book? Or would his year have been the same with or without the grants? The author does not indicate any of these details, so the reader is consequently left wondering to what extent does the book in the end reflect an “authentic” year in Horvat’s life or did he create a “specific” year, designed around the requirements of this book? Which came first for the image of each day? Important issues which remain unanswered.

|

|

Thursday,

March 4, Paris, Aquaboulevard

© Frank Horvat |

Horvat writes, in his introduction, “I took no photographs of war, of misery, of suffering or of madness; not because I am indifferent to these calamities but because I have never felt that I had either the moral justification or (in the case of war) the physical courage, to confront such situations through my lens.” His response reflects his own privilege and choices. Another photographer in a different geographical context or time, might not have such choices. Horvat, born in 1928 spent World-War II in Switzerland. We have no indication what those years were for him as a young man, who knows what makes a photographer chose to photograph or to turn away from images of conflict or calamity and who is to judge? Is there a hierarchy of value in image making?

This is a book full of the other moments that are the staple of our lives. The scenes that are often missed and left unrecorded. Each moment held, a pause, a trace as it passes consciously till the next. Moods that change – and change again. The majority of these moments, images in this book, appear to have been discovered not created, not those crucial decisive moments which many photographers patiently stake out, nothing here appears overly considered. The living appears to have come first and the photographs then knitted into that year of living. Carefully observed but never forced.

|

|

Sunday,

April 18, Cotignac, France, "La Veronique", self-portrait

© Frank Horvat

|

I speculate, how as the months passed Horvat’s relaxed eye may have become more concerned with the issue of repetition, or even boredom with the discipline of the daily need to make and record one image. No days off from behind the camera. Where was Horvat’s camera on the morning of January 1 2000, or ten days later? Finally was there time off? Or did the process continue? A new habit hard to break, or perhaps an earlier one just reinforced?

The world Horvat offers the viewer is a combination of internal and external spaces, just personal enough to give us a sense of the man behind the camera, but never crossing defined boundaries. “I did not try to reveal my sexuality or that of others, because I have never done it in the past and at my age it would be unseemly to start.” Yet it is an intimate record. A testimony that one can reveal an essence of ones’ being, without exposure. Horvat appears a solid man, comfortable in his own shoes and with his years. A man with a keen eye for detail and an apparent need for order and restraint.

|

|

Wednesday,

August 11, Reims, France

© Frank Horvat |

Daily Report is a book, which oozes with the concerns of European street photography, of the flaneur, and is bound up with the specificity of that gaze. Horvat’s eye reflects concerns which dominate twentieth century French photography, images of the street, documenting daily life. In the 1950’s he met Robert Capa and Cartier Bresson and later moved to London where he worked for both Life Magazine and Picture Post. A man whose eye has been steeped within a humanist tradition, a populist, consumed with the concerns of visual narrative. Horvat sites himself as a participant within a community of both ‘documentary’ and fashion photography. He photographs those he encounters in his report, his friends; Joseph Koudelka in his kitchen (also Spartan); Véronique Leyrit, visited over a trip to Paris; a portrait of Helmut Newton, the bridge of his glasses reflecting the identical intonation of his eye brows. Marc Riboud still photographing in Italy, Cartier Bresson, with his biographer. Photographers whose work and concerns are unique yet all who as individuals are important contributors to twentieth century European photography.

On May the fourth, Horvat visits his friend, Edouard Boubat, a photographer whose own body of work reflects similar concerns to those of Horvat. He makes a portrait of Boubat, his eyes still keen and smiling. Within weeks Boubat is dead. Horvat photographs the funeral and the coffin of his friend. The only day in the year represented by more than one image. A quiet homage in itself, as if the rhythm of his year paused and something more needed to be said. A day that stands distinct from all the others. The photograph of Boubat’s coffin in the ground so similar in form to the first image in his book of the new bath. These two photographs become inseparable, January 1st and July 2nd; cleansing and death. Looking into the grave of Boubat is a strangely intimate image, not sentimental. No different to looking into an empty bath and speculating about the bather.

The following days images reflect a sense of time pass and of loss. A sad photograph of Jean Michel Horvat, the photographers son with his son, Grégoire, followed by a lonely street scene. Nothing is said, just whispered images which connote reflection. Horvat’s book is filled with images of his family, his partner Véronique Aubry, his children and grandchildren and their friends, warm and alive. His family fill a large place in his world. These are tender and sensitive images of people used to his camera and gaze, yet they are open uncluttered images. Despite the intimacy of the relationship to him, he photographs each one of his family members with a visual separation and independence.

|

|

Friday,

May 7, La Mancha, Spain

© Frank Horvat |

Another theme, which ripples through his diary are images of animals. There is something uniquely European in the legitimacy of the male gaze on a kitten, or to be more precise uniquely French. In other visual cultures these images I speculate might be seen but left unrecorded.

Many of Horvat’s days are represented by visual ‘one liners’, seen and recorded. These are not monumental images but quietly noticed instances of the absurd. As they year progresses we encounter fragmented parts of Horvat’s body with the fantasy that by the end of the year perhaps we might have glimpsed the whole. On March 13th a hand; on April 18th a foot; a self-portrait in a hotel bathroom on June 1s reveals a torso with the face obscured by the camera; both hands, August 2nd. and then, finally in December as the year is ending, Horvat pictures himself, sick with a cold, it is as if illness has precluded all other possibilities and reluctantly Horvat has no other choice than to turn the camera on himself.

The year

ends as it began back in his home in Cotignac, France, with his partner

Véronique Aubry who worked with Horvat editing this book and the

millennium ends with the symbolic cleansing ritual of leaf burning.

Send your comments on this review to: trisha@zonezero.com