Boystown:

La Zona de Tolerancia

Book Review

by Nell Farrell

Photographs © 2000 The Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography at Southwest Texas State University. |

I slept well last night, cozy and warm in the silence and pure darkness. For breakfast I had hot coffee and sweet bread, sitting in the sun. But I feel hungover, tired, used and abused.

I feel like my body has been handled by fat, clammy male hands, my throat stings from stale cigarette smoke, and I smell flat, warm beer. I have just read through Boystown.

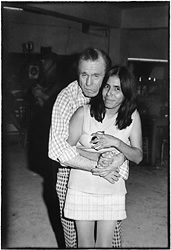

Cheap bodies, cheap clothes, cheap beer, cheap smokes, cheap sex, cheap love. None of it questioned, all of it accepted at its falsified face value. The men and women (and occasional children) in these 1970s anonymous brothel-town souvenir snapshots never considered that their image might end up in an art-photo book in post-modern, post-feminist times.

“Perhaps the power of these photographs lies in the fundamental fact that no myths are being created or sustained,” writes photographer Keith Carter in his essay at the back of the book. There is nowhere to hide anything and no one cares to anyway; they’ve come here to La Zona de Tolerancia (The Zone of Indulgence) to do the very opposite. This tempts poetic conclusions about these photographs’ expression of basic human needs and desires, and the ways and places we’ve created to fulfill them; conclusions about the universality of lust and its satisfaction among all men and among all women (though functioning very differently between the genders); about the fact that prostitution in its many forms has never been absent from the human experience; about how beauty transcends, can be found in anywhere; and the specific aesthetic and fantastic allure of a risky, underground lifestyle.

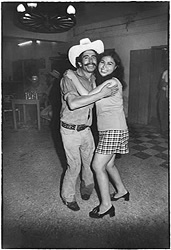

For me, this book is about the women. While it is the men who are making the moves (kissing, grabbing, fondling, and most often holding on possessively), the men who have come here from many desert miles away, the men who are looking for and paying for a service, in these photographs they are one-dimensional characters. They are obvious and pitiful. The women, conversely, are extremely present, both for the camera and apparently to themselves as well. My experience of this was similar to that of Carter: “On first viewing, I thought the women looked understandably detached. After a longer look it seems to me that they are detached, but only from their male companions; they are fully present to the photographer.” The men look pitiable because they are so glaringly unaware that the inhabitant of the body they cling to is in another world; not far away, not dreamy nor in denial, but not partaking in their fantasy--just playing the game as far as the little change purse that lies on most of the beer bottle-laden tables which foreground a majority of the images. Many of the women’s gazes could be a wink to the photographer, and to us, “can you believe this guy?”

Photographs © 2000 The Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography at Southwest Texas State University. |

Their facial expressions and body language have shockingly little to do with the physical moment. Even when they do strike a “sexy” pose, it is often with such lack of enthusiasm that it hardly seems it would satisfy the customer. None of the photos in Boystown are sexy, really. There is no pleasure, no sensuality—a hand holds a breast but there is no visible sensation, and no interaction. Although sex itself is absent from these photographs, you would never mistake one of these couples to be sitting in a roadside diner—revealed is a complex farce of romance and companionship, and exploitation and need.

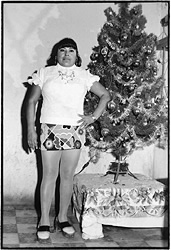

One of the early spreads in the book is a series of portraits of prostitutes in a photographer’s studio (that is, posed in front of a ratty curtain or bare wall, alone and straight on).

Here the women are far from interchangeable (although Cristina Pacheco writes in her essay that they serve as, if not feel themselves to be, “all the women and none”). Some are heartbreakingly worn down, a few are coy or expressive of their sensuality, one laughs openly, another smiles with the most kind and honest face you could find anywhere. There is a middle-aged woman in a blond wig that only serves to make her look awkward. Some women look like battered wives, used rags, abused girls. Some wear so much eye make-up that the rest of their face becomes invisible. Some look masculine, some are fat, some are having fun, some are beautiful.

You can’t help but wonder where they live, what they think about. You can’t help but wonder how integral our physical experiences are to our spirit. Is it possible to overcome this hard physical life or, although you maintain your distance and your memories, does it define you? Do so many of the women in these photographs look uncomfortable for the impossible expectation of a glamorous pose in the farthest place on Earth from Hollywood? Is it the itchy plastic get-up they have squeezed themselves into? Is it the camera, hired by the client, capturing them in a “two-dollar universe”? Or is it perhaps their very life that makes them uneasy in their own skin?

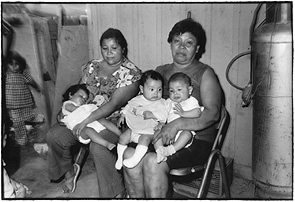

The photographers who circulated in these whorehouses and the women who worked there probably saw each other night after night; there is no artifice between them, even in this setting that begs it. In some of the images there seems to be a tenderness or a familiarity between the client and the prostitute, and I let myself imagine that they have a deeper relationship. But despite these aspects that let those depicted exist as individuals, after pages and pages of drunk-man-grappling-half-naked-woman shots, they start to look the same. On the very page where I felt I couldn’t take it anymore, having reached some level of tedium or surfeit, the nature of the photographs changed. A woman with a bandaged head lies in her bed, alone. In another children overflow the laps of what could be a young mother and her own mom. Interestingly, here the women’s gazes are shrouded; not cold, but not inviting. This is their private world and they have no reason to let us in.

Photographs © 2000 The Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography at Southwest Texas State University. |

Bill Wittliff, the collector of these anonymous images, comments that there are more: “along with the standard party pictures there were portraits of the prostitutes, snaps of street urchins, busboys, musicians—indeed a cross-section of that whole cloistered world....” As a historical or sociological study this book would be more complete if the rest of the “town,” and more of the private lives of the sex workers, were revealed. We are now so used to the tell-all, show-all manner of investigating the “other side” that the book in fact seems strangely trapped within the walls of the brothels. This collection of photographs thereby becomes a challenge to the reader. If you are willing to take on what they show, and still try to understand what they don’t, this is a powerful book. The essays allude to the rest of the place, and to the stories of the characters, but the photographs force us to understand the defining factor: the night. And yet, in that context, “... the humanity we see in these faces seems to compel us to look squarely at whatever uncomfortable truth lies beyond” (Carter).

Photographs © 2000 The Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography at Southwest Texas State University. |

If I had read Keith Carter’s description of Boystown the place before looking at the photographs, the business and the lives depicted would have been clearer cut, and more horrible. Before I really understood what kind of place this was, and only knew that it was a cluster of brothels on the Mexico side of the Texas-Mexico border, I could imagine life stories for the women, ponder US-Mexico cultural dynamics, even enjoy the beautiful reproduction of these salvaged photographs. Carter’s description, though, is chilling. “It was surrounded by high adobe and cinderblock walls topped with razor-wire and broken glass.... At the lower end of the scale were the cells—along walls of repeated doors and windows—and sitting outside of every one a prostitute, each one older, uglier than the one before her.” Heavier on the bitter than the sweet, even as these photographs are of a world that revolved around what is love and sacrifice, they are witness to the harm we do in our desperate search to dull the pain of being.

Buy this book at Amazon.com and support ZoneZero.

Boystown:

La Zona de Tolerancia:

With esssays

by Cristina Pacheco, Dave Hickey, and Keith Carter Afterword by Bill Wittliff

Aperture, in association with the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and

Mexican Photography at Southwest Texas State University, 2000

Send your comments on this review to: ilpostino@zonezero.com