|

by Fernando Castro

Español

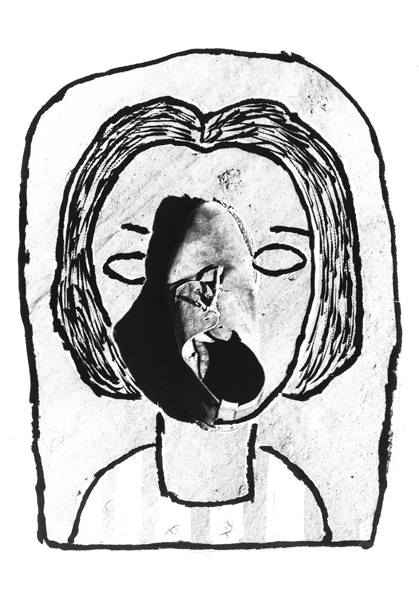

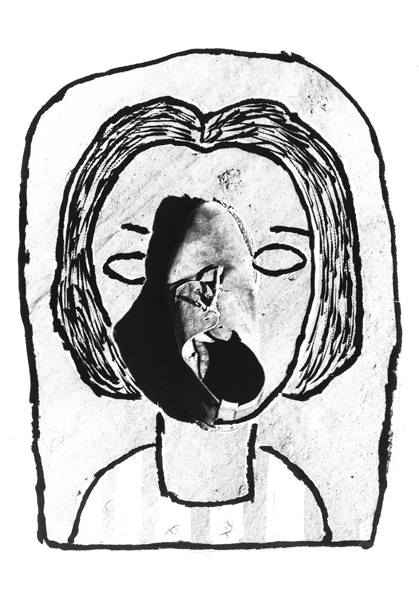

Menina do Sapato © Geraldo de Barros

Menina do Sapato © Geraldo de Barros |

The first time I saw Geraldo de Barros’s Menina do Sapato was in the catalog of the exhibition of the first Latin American Colloquium of Photography: Hecho en Latinoamérica (Mexico, 1978). Had I been Brazilian perhaps I would have recognized the author’s name as that of a renowned artist. But alas, I was a naïve young man and I innocently assumed that the author was another enthusiastic youngster experimenting with the medium. In said catalog there is no date for the work, so I got the impression that it was a recent work. At the time I did not really think about art, I just liked it or disliked it, and occasionally was able to voice a few opinions about it. What I liked about Menina do Sapato was the cleverness with which the opening of the shoe had been made to double as a gaping mouth on the cartoon-like face of a little girl vaguely resembling Mafalda, Periquita, or La Pequeña Lulú.

Although de Barros could have staged the old shoe for building the image, more than likely it was an object he found half-buried in the sand. The shoe part of the image agreed with the way I had learned to engage the medium of photography; namely by looking, finding and capturing. So it was easy to imagine myself finding the old shoe and photographing it. However, de Barros’s work was teaching me then that I could also draw on my found images by scratching the negative and painting over it. However, ten years went by before I dared to permanently alter my negatives the way he had because in my mind that alteration was tantamount to damaging something almost as precious as reality itself. Instead, I modestly began experimenting by cutting my prints to make photo-collages. I never exhibited these collages but a few friends who liked them ended up owning them.

I also saw a social commentary and political dimension in Menina do Sapato that–not knowing the artist– I understood could have been just my own interpretation. There is something very destitute about a single old discarded shoe acting as the girl’s open mouth. It is as if the abandonment and poverty of the shoe nuanced the drawing of the girl so that she was no longer the middle-class Mafalda, Periquita, or Lulú. Her disheveled hair, roughly drawn on the negative with a sharp tool, made her look like one of those indigenous homeless girls that roam the streets of Lima, Mexico City or São Paulo, clinging to their mother’s skirts and extending their small hands to the passersby pleading, “Señor, una ayuda por favor.” That open mouth that in Edvard Munch’s Scream (1893) expressed a sort of existential howl of despair, in Geraldo de Barros’s Menina was something as basic and passive as hunger, or as critical and active as asking, “why?” The hollow of that shoe is so very dark, deep and loud.

In 1992 I started writing the essay Crossover Dreams for the book Image and Memory: Photography from Latin American 1866-1994 (University of Texas Press: Austin, 1998). It was then that I perused the Hecho en Latinoamérica catalog once again and took a second look at Menina do Sapato. I wanted the image to accompany my text, but how would I find it? Fortunately, somebody had the great idea to include in the back of said catalog a list of the participants and their address. Still thinking that Geraldo de Barros was a young man I wrote to him speculating that perhaps by then he had become a lawyer, a taxi driver, or both, and might not even be doing photography anymore. To my surprise, a month later I got a letter from his daughter Fabiana de Barros in which she thanked me for the interest in her father’s work and cordially agreed to send me the picture for use in my essay. It was only when I received the print that I found out that Menina do Sapato was made in 1949! Who was Geraldo de Barros? At the time, it was not possible to quickly google and find out who’s who, so answering the question became a very slow process.

Although I did not know it then, the reason Geraldo had not answered my letter himself is that by that time, he had suffered a couple of traumatic strokes that impaired his speech and motor skills. My letter had arrived at a turning point in the dissemination of his work. Fabiana, who is also an artist in her own right, had taken it upon herself to have her father’s oeuvre receive the recognition it deserved. She was instrumental in arranging Geraldo de Barros, Peintre et Photographe, a major retrospective at the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1993. In 1994, she helped organize another exhibit at the Museum da Imagem e do Som de São Paulo: Geraldo de Barros, Fotógrafo. It was thanks to this last exhibit that I came upon the only book about him: Fotoformas, Geraldo de Barros (Raízes: São Paulo, 1994). Both shows were based on the seminal 1950 Fotoformas exhibit at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo her father himself had put together when he was only twenty-seven years old.

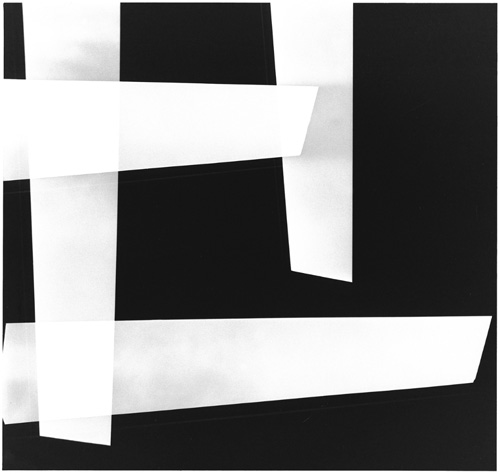

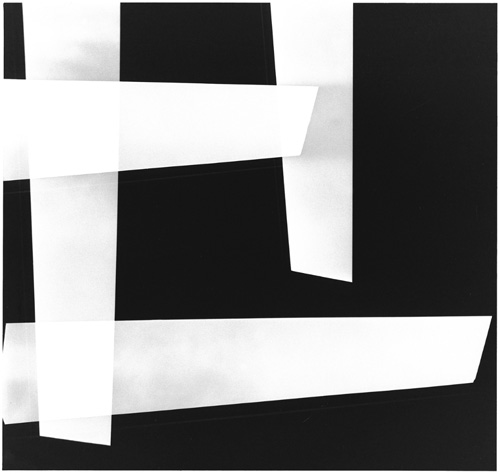

Fotoforma © Geraldo de Barros

Fotoforma © Geraldo de Barros |

The book that bore the same name as the exhibit, Fotoformas, Geraldo de Barros, contained some installation photographs of the 1950 exhibit and among the works that appeared in them was Menina do Sapato. He showed it almost as a sculptural object: the print cut along the edge of the image and mounted on a solid support to stand by itself. The presentation vaguely resembled the foto-esculturas that I understand can still be made to order somewhere in Mexico City. In addition, the book revealed a plethora of other kinds of photographic techniques with which de Barros had experimented: multiple-exposures, cut-negatives, pinhole photography, etc. Some works were labeled “superposição da imagens no fotograma” –a phrase in which the term fotograma turned out to be a false cognate for “photogram.” Geraldo himself never used this terminology to describe these works. Although in the French translation the aforementioned book used a better phrase --“superposition a la prise de vue”-- my confusion had begun.

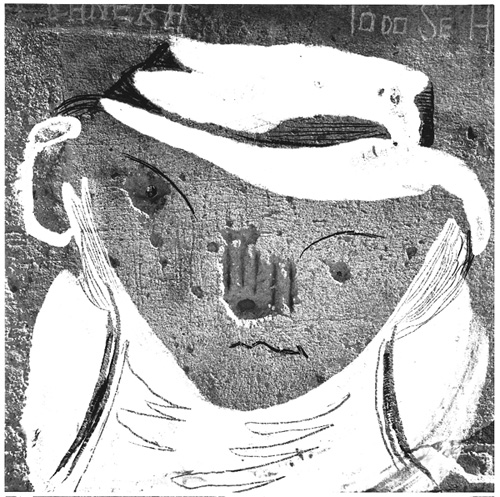

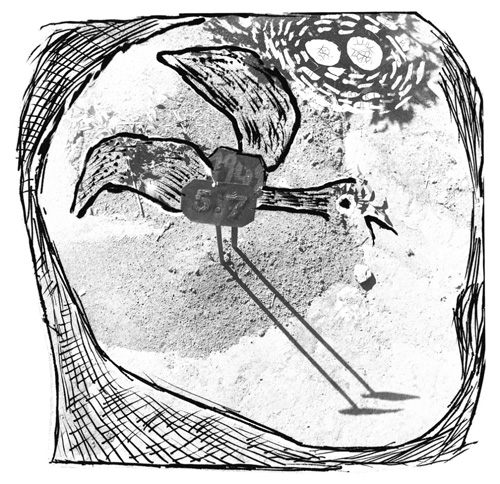

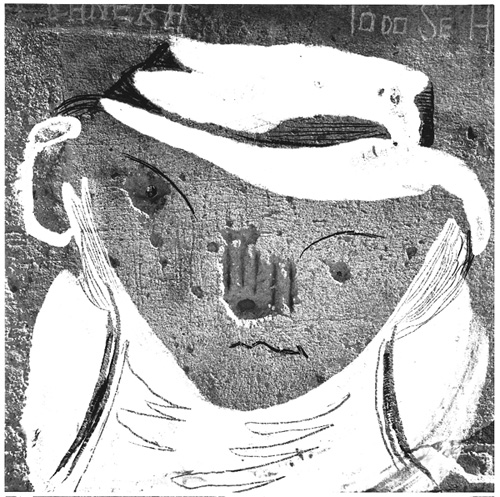

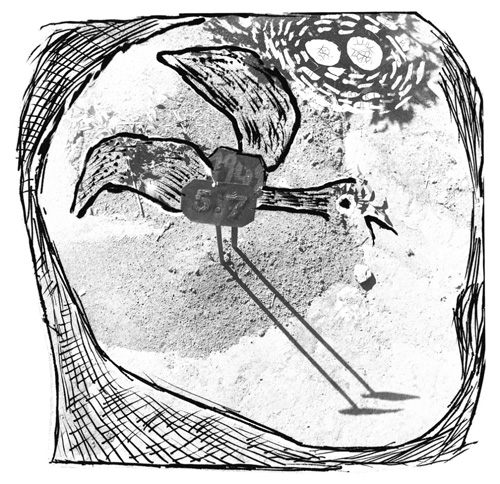

The confusion originated in the fact that a Portuguese dictionary defines “fotograma” as “Cada uma das imagens registradas en filme fotográfico ou cinematográfico.” Needless to say, the English meaning of the word is much narrower: namely, “a photographic image produced without a camera, usually by placing an object on or near a piece of film or light-sensitive paper and exposing it to light.” (From built-in dictionary in my Microsoft Office software). To add to the confusion was the fact that many fotogramas were very abstract and geometric and really looked like photograms. I believe I was not the only writer who took some of Geraldo’s works to be photograms, but I did not pay too much attention to the issue because the ones that most captivated me were the ones described as “desenho sobre negativo com ponta-seca e nanquim.” These last works resembled Menina do Sapato in that Geraldo made them by scratching and painting the negatives: Homenagem a Picasso (1949), Homenagem a Stravinsky (1949), O anjo (1948), and Cemitério do Tatuapé (1949).

Homenagem a Picasso © Geraldo de Barros

Cemitério do Tatuapé © Geraldo de Barros

|

|