Galerías

Resultados 276 - 300 de 1334

|

Autor:Mariko Takeuchi

Ensayo de Maryko Takeuchi curadora invitada de "Spotlight on Japan" para Paris Photo 2008

Part 1 Part 2

Introducción

En japonés, la palabra para fotografía es “shashin”. Se compone de dos ideogramas “sha”, que significa reproducir o reflejar, y “shin” que significa verdad. La raíz griega de la palabra fotografía significa “escribir con luz” (graphos, escribir, y photos, luz). Por lo tanto, dentro de la mentalidad japonesa, el proceso mismo consiste en capturar la verdad, o esencia de algo y “copiarla” sobre una superficie. Como consecuencia, el resultado debe siempre contener algún elemento de verdad. Desde la aparición de la fotografía, este modo de ver las cosas, se ha convertido en un lugar común en todo el mundo, sin embargo, en pocas lenguas se expresa con tal claridad. Si partimos de la premisa de que la fotografía japonesa es el fruto de múltiples reacciones, que van desde la empatía a la desconfianza, y de este proceso de “reproducción de la verdad”, es posible entender mejor esta asombrosa diversidad.

Al considerar la fotografía japonesa en su totalidad, es evidente que un gran número de artistas, tienden a expresar sentimientos de incomprensión y ambigüedad hacia la realidad y el mundo, en lugar de intentar descifrarlo y analizarlo objetivamente. En “Imperio de los Signos”, Roland Barthes señala que la cultura japonesa ganó su libertad al liberarse de los signos que contiene. De alguna manera esto también puede decirse de la fotografía. La fotografía no es una conclusión, sino un perpetuo cuestionamiento. En este sentido, Barthes acertó al comparar a la fotografía con el arte del Haiku en “La Chambre Claire”.

Al poseer tal diversidad de aproximaciones, los fotógrafos japoneses han demostrado que no existe “La Verdad”, y continúan haciendo la pregunta fundamental, a saber: Que es lo que la fotografía puede reproducir y que es lo que elude los intentos de reproducción. Por ejemplo, desde los años 70, Nobuyoshi Araki, uno de los fotógrafos mas eminentes del Japón, lejos de enfocarse en el antagonismo entre verdad y ficción, ha tratado continuamente de demostrar de todas las maneras posibles, que la fotografía es verdad y ficción al mismo tiempo. De manera similar, Daido Noriyama, apoyando la idea de Warhol de que la fotografía no es mas que una copia, también captura con una delicada sensibilidad, el elemento de la remembranza que habita dentro de la fotografía. En los años 80, aparecieron fotógrafos como Naoya Hatakeyama que vieron su trabajo como un intento de analizar y entender al mundo. Al mismo tiempo, la corriente “intimista” expuesta por fotógrafos como Rinko Kawauchi, quien logra capturar la belleza de la vida cotidiana, perdura en innumerables variaciones formales.

Una de las características de la fotografía japonesa es el rol cada vez más importante del material en que se imprime. Ya sean generales (revistas) o especializadas (libros de fotografía), las publicaciones han sido un vehículo vital para los fotógrafos y su trabajo. De hecho, en ningún otro país existe tal riqueza de publicaciones. Este fenómeno se explica en parte por la ausencia de una red de galerías o un mercado fotográfico establecido. Pero esto también puede atribuirse a la peculiar historia de los procesos de reproducción en nuestro país y la cultura que lo rodea. Específicamente, la fuente puede ubicarse en la época Edo (1603-1827), con el desarrollo de las incomparables técnicas de bloques de madera, la belleza de las impresiones Ukiyo-E y su inmensa popularidad en el Japón.

En años recientes, el trabajo de un creciente número de fotógrafos japoneses se ha dado a conocer individualmente en Europa y los Estados Unidos de América, pero las oportunidades de presentar una visón panorámica de la historia de la fotografía japonesa son extremadamente raras. La exposición “Nueva fotografía Japonesa”, realizada en Nueva York en 1974, fue una verdadera precursora. La llegada del siglo XXI ha traído una aproximación mas holista a la fotografía, y en este contexto, la gran retrospectiva titulada “La Historia de la fotografía Japonesa” del Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston en el 2003 fue un hito. Desde entonces, ha existido un creciente número de exposiciones y publicaciones en el Occidente. La edición 2008 del Paris Photo en la que Japón es el país homenajeado, es el fruto de un largo proceso de maduración.

La fascinación de Europa con el Japón durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX no fue solo una moda pasajera. Su influencia no solo fue evidente el arte occidental, en especial en la escuela impresionista, sino también en términos de estilo de vida. Esta moda se impuso con la presencia del pabellón japonés en la Exposición Universal de 1867 en Paris. Siento cuarenta y un años después nos encontramos con una extensa revisión de la fotografía japonesa, en una escala nunca antes vista en Francia. Es mi mayor deseo que hoy, mas que nunca antes, en una época de transición debida al surgimiento de la tecnología digital, que este evento no sea solamente percibido como algo “exótico”. Espero que nos estimulara a redescubrir todas las posibilidades ofrecidas por el medio fotográfico, e impulse su energía creativa.

Presentación General

La fotografía llegó a Japón en 1848, exactamente nueve años después de su nacimiento en Francia y la invención del daguerrotipo. Como muchos otros países no occidentales, Japón se volvió el “objeto” de imágenes cargadas de exotismo. Pero las cosas cambiaron rápidamente cuando los japoneses se convirtieron en “sujetos” capaces de tomar fotografías.

Para 1862, los fotógrafos japoneses habían establecido estudios para tomar retratos en los puertos de Nagasaki y Yokohama, y en la mitad del siglo XIX, se vió un desarrollo gradual de la industria de fabricación de cámaras en Japón. A comienzos del siglo XX, se incrementó el número de fotógrafos aficionados en todo el país. Aunque inspirados en la estética tradicional japonesa, la fotografía “artística” (incluido el Pictorialismo), apenas comenzaba.

En los años 30, recomenzó una evolución clara hacia la fotografía moderna. El cambio fue marcado por un evento simbólico: La creación, en 1932 de “Kôga” una publicación cuyo título se compone de dos ideogramas que significan “luz” (ko) y “dibujo” (ga). Al abandonar el término shashin (que implicaba la búsqueda de la verdad en el acto fotográfico), las principales figuras detrás de la publicación, Yasuzô Nojima, Iwata Nakayama, y en especial Ihei Kimura, proclamaron su deseo de adherirse a la modernidad a través de su trabajo con la luz. Kimura, un maestro de la Leica, quien a menudo es llamado el “Cartier-Bresson japonés”, jugó un papel muy importante durante el periodo de la posguerra, como líder del circulo fotográfico del país. Pero aun antes de la guerra, surgieron fotógrafos aficionados, tales como Nakaji Yasui u Osamu Shihiaha, no sólo en Tokio, sino también en los alrededores de Osaka, en donde tuvieron muchísima actividad explorando la vanguardia.

Con la desolación y caos que siguió a la derrota del Japón en la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el foto reportaje, que sirvió como testimonio de la desesperada situación de la población, dominó la escena durante varios años, sin embargo hubo varios esfuerzos coincidentes, pero independientes entre sí, de buscar nuevas formas de expresión fotográfica. A este respecto, la creación, en 1959 en Tokio, de la agencia “VIVO”, por Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, Ikko Narahara y Kikuji Kawada, marcó el nacimiento de una nueva generación de fotógrafos cuya intención era ir mas allá de la simple experimentación para establecer un oficio real. Teniendo un ojo agudo y critico de la realidad, conceptos claros, un sentido real de la composición y el encuadre, y al mismo tiempo un gran énfasis en lo simbólico, este grupo ejerció una tremenda influencia en la siguiente generación.

En el preámbulo a los juegos olímpicos de 1964 en Tokio, Japón pasaba por un periodo de tremendo crecimiento económico, que proporcionó un terreno fértil para los nuevos fotógrafos japoneses en los campos del fotoperiodismo y la publicidad. Sin embargo, en la segunda mitad de los años 60, nuestro país, al igual que muchos otros sufrió un gran revuelo por la oposición a las políticas públicas prevalecientes en la cultura y la economía, mediante el activismo estudiantil y las violentas protestas contra el tratado de seguridad entre el Japón y los Estados Unidos. En 1968, el año emblemático de la lucha, se publicó el primer número de “PROVOKE”, cuyo evocativo subtitulo rezaba “Documentación Incendiaria para el Nuevo Pensamiento”, y resonó en todos los círculos fotográficos del Japón. Entre sus miembros estaban Takuma Nakahira y Koji Taki, junto con Daido Moriyama, quien se unió a la publicación en su segundo número. Estos fotógrafos se embarcaron en un proceso de deconstrucción radical de las reglas y la estética de la fotografía clásica, cuyos estilos fueron llamados a menudo “Are, Bure, Boke” (borroso, desenfocado).

En ese mismo año, 1968, un grupo de jóvenes fotógrafos comenzó a ser llamado “Konpora”, una contracción estilizada japonesa de “contemporáneo”. Tenia su raíz en una tendencia definida por la exposición de 1966: “Fotógrafos contemporáneos: Hacia un paisaje social” en la George Eastman House. A primera vista, las imágenes producidas por el grupo “Kompora”, marcadas por su neutralidad, composición y enfoque en la insignificancia de la vida cotidiana, aparecen como la antitesis de los del grupo “PROVOKE”. No obstante y a pesar de la disparidad en los temas de inspiración, todos estos trabajos son una reacción en contra de las metodologías fotográficas dominantes en ese entonces, así como un reflejo de la ambigüedad prevaleciente en la época. Yutaka Takanashi, uno de los entonces llamados “Konpora” era a la vez un colaborador activo de “PROVOKE”.

Para presentar su trabajo al público, los fotógrafos de la época, tenían pocas opciones aparte de asistir a las publicaciones especializadas tales como “Asahi Camera” o “Camera Mainichi” o ir a galerías asociadas a Canon, Nikon u otros fabricantes de equipo fotográfico. Para poder superar esta situación, algunos jóvenes fotógrafos decidieron, en la década del 70, abrir sus propias galerías. Comenzando en Tokio, esta iniciativa pronto arraigó en todo el país. Una de éstas, “Image Shoot Camp” ha permanecido como una leyenda desde entonces, debido a la actividad de fotógrafos como Daido Moriyama y Keizo Katajima.

La primera galería especializada en la venta de impresiones fotográficas “Zeit Foto Salon”, fue inaugurada en 1978.

Pero esto no bastó para dar suficiente ímpetu para movilizar el mercado nacional, hasta el día de hoy, el número de fotógrafos que tienen contrato con galerías que se encuentran en posición de comercializar su trabajo, es muy limitado. La mayoría sigue exponiendo en galerías independientes o en espacios rentados por ellos mismos. Esta continúa siendo una de las característica peculiares de la fotografía japonesa.

Sin embargo, la “burbuja económica” de los años 80, proporcionó un ambiente favorable para la fotografía japonesa, que pasaba por un periodo de profunda transformación. Varias innovaciones tecnológicas (especialmente el lente AF y las cámaras compactas) llevaron a la fotografía a un nivel de popularidad nunca antes visto. En los años noventa, las nuevas generaciones desarrollaron una verdadera pasión por la fotografía, en particular por la fotografía de una naturaleza muy personal.

Alrededor de 1990, se inauguraron varios museos de fotografía en todo el país, así como el establecimiento de un sistema para medir el valor histórico y artístico del medio. Esto explica cómo, a pesar de tener un mercado débil, la fotografía japonesa ha desarrollado una fisonomía propia, y se ha institucionalizado, pero al mismo tiempo se ha impuesto como un fenómeno de masas.

Durante este periodo, ha surgido un número de fotógrafos con series en las que se cruzan los caminos del arte y la fotografía, basada en conceptos muy sólidos. Pueden a grandes rasgos, dividirse en dos grupos: uno que usa la fotografía como su medio preferido de aproximarse al mundo desde un punto de vista individual; el otro trabaja con este medio para acceder a lo imaginario y trascender el tiempo y el espacio. En el primer grupo, tenemos a Naoya Hatakeyama, quien trabaja utilizando una gran variedad de ángulos para comentar sobre la evolución del paisaje urbano, a Toshio Shibata quien revela las bellezas escultural de las presas y otras obras públicas anónimas, a Ryuji Miyamoto, quien captura los restos de la civilización en objetos y estructuras en estado de descomposición y a Taji Matsue, quien utiliza la fotografía aérea para resaltar la topografía de lugares específicos. En el segundo grupo se encuentran: Hiroshi Sugimoto, cuya obra puede ser vista como un comentario critico de la historia y la temporalidad, mientras que Yuki Onodera, quien ha publicado series de imágenes muy diversas puede decirse que ha liberado la imaginación y le ha quitado todo peso.

Identidad, el cuerpo y la sexualidad –todas ellas cuestiones humanas fundamentales- se encuentran entre los temas que dominan la fotografía japonesa. Esto es especialmente cierto respecto a Miyako Ishiuchi, pionera de las fotógrafas japonesas. Durante los últimos 30 años ha trabajado constantemente en los efectos del paso del tiempo en la piel humana y el ropaje. Ryudai Takano explora la vida cotidiana para traer a la luz ocultas manifestaciones de ambigüedad sexual y erotismo. Al superponer múltiples retratos de miembros de un determinado grupo de personas, Ken Kitano intenta identificar los parámetros de aquello que constituye la individualidad, de aquello que hace que yo sea “yo”. Mientras tanto Tomoko Sawada se atavía y se transforma en una multitud de diferentes personajes para cuestionar la pluralidad de nuestra identidad. Finalmente, Asako Narahashi se retrata inmersa en las aguas de océanos y lagos para desvanecer la imagen de estabilidad que otorgamos al mundo, revelando sus cualidades efímeras y frágiles.

Resulta difícil asignar una sola etiqueta estilística al trabajo de todos estos fotógrafos, sin embargo, más allá de sus contribuciones visuales e intelectuales, la mayoría tiene la capacidad de cuestionar nuestras convicciones y prejuicios respecto a una gran variedad de cuestiones en una época en la que las nociones de “límites” y “valores” son tema de interminables debates, y no resulta sorprendente que estos trabajos sean objeto de gran interés. No cabe duda de que esto es especialmente importante en la designación del Japón como el país invitado de honor en el Paris Photo de éste año.

La Sección “Manifestación” de Paris Photo 2008

En 1989, se cumplió el 150 aniversario de la invención de la fotografía. Ésta fue una época de prosperidad sin paralelo en el Japón y fue durante aquellos años que muchas instituciones culturales fueron fundadas en el país, varias de ellas especializadas en la fotografía: la primera fue el Museo de la Ciudad de Kawasaki, luego el Museo de Arte de Yokohama, que fundó su departamento de fotografía y finalmente el Museo Metropolitano de Fotografía de Tokio. Al mismo tiempo, la inmensa popularidad de la cámara compacta entre el público en general, trajo un auténtico “boom” entre la juventud del país. Se creó un número de eventos enfocados hacia los jóvenes, en particular dos grandes competencias: “El Nuevo Cosmos Fotográfico” y “Hitotsuboten”. Hasta entonces, las fuerzas detrás de la fotografía habían sido las revistas especializadas y las galerías corporativas, y éstos nuevos eventos dieron a los jóvenes la oportunidad de mostrar su trabajo. Otro factor fue el creciente número de galerías dedicadas a la fotografía, lo que permitió el florecimiento del talento experimental y su liberación de los convencionalismos y límites clásicos.

Es en éste contexto y durante la pasada década, en que surgieron los jóvenes fotógrafos presentados no solo en la sección “manifestación” sino en todas las secciones del festival. Lejos de estar limitados por los criterios de lo que constituye el “gran arte”, éstos trabajos exploran todas las posibilidades ofrecidas por el medio fotográfico, que es visto como uno de los muchos vehículos de la expresión creativa. Por ejemplo, Mika Ninagawa, cuyo trabajo es extremadamente popular entre la juventud japonesa, no se basa en un sentido estético establecido. Los valores que ella invoca pertenecen a la “subcultura”, y son su punto de partida para la creación de un mundo muy personal, caracterizado por una paletilla de colores muy brillantes. La cualidad teatral de su obra se ha reforzado en sus últimas creaciones –películas inspiradas en los cómics “Manga”. Midori Komatsubara también halla inspiración en el “Manga”, específicamente en el subgénero que trata del amor entre los jóvenes. Ella captura la ambigüedad que habita los cuerpos de las jóvenes que se mueven entre la fascinación y la fantasía. Confrontando el rechazo de sus propios deseos, Yumiko Utsu utiliza objetos cuidadosamente arreglados en imágenes “kitsch” en las que ella logra revelar sentimientos particulares de la cultura juvenil japonesa –el infantilismo y la crueldad-. Mientras tanto, Masayuki Shioda se mueve con facilidad de una actividad a otra, colaborando tanto con la industria musical como con la las revistas de cultura juvenil.

Para la segunda mitad de los noventa, ésta joven generación gradualmente se había establecido con trabajos en los que se cruzaban los caminos de la fotografía pura y otras formas de expresión artística. Muchos trabajos aparecieron a color y estaban principalmente preocupados en expresar el sentimiento de inestabilidad que llegó con el estallido de la burbuja económica y una prevaleciente sensación de que la vida cotidiana se hallaba amenazada de alguna manera.

Esta visión del mundo, que aparece como si fuera vista a través de anteojos para una persona miope, es particularmente aguda en las imágenes de Rindo Kawauchi. Iluminadas por una luz suave y sutil, parecen cálidas a primera vista, pero también manifiestan una sensación de amenaza. Ella y Mika Ninagawa luchan por capturar lo que es universal en las personas y las cosas con una detallada observación de su medio ambiente inmediato. Mientras tanto Nobuo Asada se sumerge en el océano para tomar sus fotografías con la intención de colocarse como un vivo ejemplo de la inevitable interacción entre el “sujeto fotógrafo” y el “objeto fotografiado”.

Top

Aunque éstos artistas adoptaron una visión del mundo dominada por el close up, otros trabajos comenzaron a aparecer hacia el año 2000, en los que las perspectivas aparecen “aplanadas” y aunque las nociones de “cercano” y “distante” son cuestionadas, se les da una importancia igual. Esto es un reflejo de una de las características de nuestros tiempos, dominados por la tecnología digital, la cual procesa la información sin importar la jerarquía de los datos. Por ejemplo Gentaro Ishizuka eligió a la tubería de Alaska como tema. Se trata de la segunda tubería más larga del mundo y él no se detiene por las dificultades presentadas por el tamaño del proyecto. Sus imágenes son tan neutrales, que casi nos desaniman. Esta aproximación tan contemporánea es similar al trabajo de Wolfgang Tillmans en su serie “Concorde”, en la cual el fotógrafo ve todas las cosas sin ningún rastro de juicio de valor.

Dicho esto y sin quedar suscrito a ninguna “tendencia” contemporánea, numerosos fotógrafos continúan haciendo una pregunta fundamental para su medio de expresión elegido: ¿Qué es lo “fotografiable” y qué no? Keisuke Shirota pega pequeñas fotografías a un lienzo y utilizando pintura acrílica, prolonga la imagen más allá de su encuadre original, resaltando el intervalo entre lo visible y lo invisible, lo imaginario y lo real. Akiko Ikeda utiliza imágenes de personas, recortándoles algunos fragmentos, con un giro humorístico similar a la iluminación a contraluz, ella transforma la fotografía bidimensional en un objeto tridimensional. Mientras que éstos dos artistas exploran los límites del encuadre desde el exterior, otros, como Takashi Suzuki, Naruki Oshima, Nobuhiro Oshima y Mamoru Tsukada, trabajan desde el interior para buscar la pequeñas grietas en la barrera entre lo visible y lo invisible.

Hay otros que tratan este tema específicamente en lo que respecta a la memoria, que no puede ser vista por el ojo, trabajando con recuerdos y eventos históricos ligados al lago Biwa, el más grande del Japón, Nao Tsuda teje una delicada narrativa hecha de paisajes e historias. Tomoko Yoneda es la artista con la trayectoria más larga de entre todos los presentados en la sección “Manifestación”. Ella toma fotografías muy detalladas de paisajes en la escena de eventos históricos o accidentes. De esta manera, ella explora los límites de la representación visual, tanto desde el punto de vista estético como desde el ético. En nuestra era digital, la imagen se ha convertido en un producto de “consumo de alta velocidad”, y éstos fotógrafos están en contacto inmediato con los eventos mundiales como nunca antes. La seriedad y consistencia con la que continúan su búsqueda y sus elecciones artísticas son tales, que el espectador siente la necesidad de tomar una pausa para reflexionar.

Editores Japoneses

Resulta imposible sobrestimar el papel de las publicaciones impresas en la evolución de la fotografía japonesa. Aún antes del comienzo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial hubo un gran número de publicaciones dedicadas a la fotografía en el Japón. Pero fue en el período de la posguerra y la gran popularidad de cámaras fabricadas en el país lo que trajo una abundancia de revistas especializadas, dignas de mención fueron “Camera”, “Photo Art” y “Asahi Camera”, entre otros, dando aún mayor ímpetu a la actividad fotográfica. La mayor parte de éstas revistas, no sólo publicaron artículos y asesoría técnica a los aficionados, también proporcionaron información sobre la fotografía Occidental, la obra de fotógrafos extranjeros. Muy pronto, éstas se convirtieron en trampolines para los fotógrafos profesionales del Japón. En los primeros tiempos, los libros fotográficos fueron publicados en colaboración con éstas revistas especializadas. Para la segunda mitad de 1950, aunque en un reducido número, los libros se convirtieron en medios de expresión independientes. Los sesentas y setentas vieron nacer una serie de obras maestras “Barakei” (Terrible Experiencia con Rosas) de Eikoh Hosoe en 1963, “Chizu” (El Mapa) de Kikuji Kawada en 1965 o “Senchimentaru na tabi” (Viaje Sentimental) de Nobuyoshi Araki en 1971.

En 1980 algunas de las publicaciones que habían tenido un papel preponderante en los círculos fotográficos perdieron su ímpetu. La revista “Camera Mainichi” cerró sus puertas en 1985. Cada vez más fotógrafos recurrieron a los libros para difundir su trabajo. Eran apoyados por muy pocas editoras, tales como Michitaka Ota de Sokyusha. Él supervisaba la publicación de trabajos de muchos fotógrafos, algunos bien establecidos, otros aún desconocidos, incluyendo al legendario “Karasu” (Cuervos) de Masahisa Fukase en 1986. Hacia el final de los ochenta, el fotógrafo Osamu Wataya fue nombrado director artístico de la compañía de moda “Hysteric Glamour”. En la primera mitad de los noventa, supervisó la publicación de la serie “Hysteric”, que llevó de nuevo a Daido Moriyama al centro de la escena fotográfica. Hasta hoy en día, Wataya continúa publicando libros de fotografía que sobresalen por su inventivo diseño.

Las cinco casas editoras presentadas en la Exposición Central de Paris Photo tuvieron sus comienzos en el contexto mencionado anteriormente. Hoy en día son los socios más activos para los fotógrafos en términos de ayuda para concebir y publicar sus materiales personales. Lejos de ser considerados como meras copias de tal o cual trabajo o como simples canales de información, a sus ojos, constituyen un vehículo esencial para la fotografía, por supuesto teniendo en cuenta que la fotografía es en su origen, una técnica de reproducción. Hay un gran número de notables fotógrafos en Japón hoy en día, pero muy pocas galerías dispuestas a comercializar su trabajo. He aquí el por qué la actividad de estos editores es crucial, no sólo en términos de apoyar su trabajo, sino también para la fotografía japonesa en su conjunto.

Fundada en 1984, Toseisha el la más antigua de estas 5 casas editoras. Desde su comienzo, ha publicado de manera constante la obra de fotógrafos japoneses, tanto profesionales como aficionados. Su presidente Kunihiro Takahashi, es también el editor en jefe y está tan dedicado a su trabajo que le da seguimiento personalmente, hasta donde es humanamente posible, a cada etapa del proceso, desde la revisión de las hojas de contacto hasta el mezclado de las tintas para la impresión. Por ejemplo, le llevó diez años perfeccionar la edición refinada y ampliada del trabajo casi mítico “Zokushin, Dioses de la Tierra” de Hiromi Tsuchida, originalmente publicada en 1976.

Los catálogos de Little More, casa editora fundada en 1989, ofrecen una gran variedad de libros que tratan todos los aspectos de nuestra cultura. Después de la publicación, a mediados de los noventa, de los trabajosde Takashi Homma y Yurie Nagashima, esta editorial comenzó a publicar más libros del trabajo de fotógrafos jóvenes, como Kayo Ume, quien ganó el premio Kimura en el 2006 con su libro “Umeme”, teniendo un éxito asombroso al vender más de 100,000 copias. Utilizando su propio estilo y diseño, Ume captura momentos que aparentan una normalidad cotidiana, pero creando imágenes que parecen vistazos furtivos que son a veces humorísticos y a veces ligeramente pérfidos. Su éxito encarna de muchas maneras el aspecto más “popular” de la cultura fotográfica japonesa. El caso de Ume está lejos de ser una excepción, muchos fotógrafos han conseguido el respeto de los aficionados y el aplauso del público no a través de la exhibición de impresiones originales sino de la publicación de libros.

El primer volumen de la obra “Ikite iru” (Vivo) de Masafumi Sanai, ha tenido un impacto decisivo en la expresión fotográfica japonesa de los últimos 10 años. Fue publicado en 1997 por Seigensha, que solo tenía dos años de fundada en ese entonces y cuya preocupación recaía en las artes visuales en su conjunto. Hideki Yasuda, su director, quedó pasmado al ver el trabajo de Sanai y el increíble rigor que subyace en su aparente crudeza. Después de descubrir a éste artista, publicó a otros fotógrafos, incluyendo a “Me no mae no Tsuzuki” de Jin Ohashi, una obra especialmente sólida en la que el artista muestra, de una manera casi carnal, la discontinuidad entre el traumático intento de suicidio fallido de su padre y la banalidad de la cotidianeidad.

La editorial más poderosa en el campo de los libros fotográficos en Japón es Akaaka Art Publishing. Fue fundada en el 2006 por Kimi Himeno quien llegó de Seigensha, en donde trabajó como editora de fotografía en sus comienzos. Como consecuencia de haber conocido tanto a Sanai como a Ohashi, Himeno se percató del inmenso poder de su trabajo al explorar las profundidades de la vida y de la muerte. Ella supervisó la publicación de una gran cantidad de libros, en especial del trabajo de los fotógrafos jóvenes. En el 2007, el premio Ihei Kimura fue compartido por Leiko Shiga por “Canario,” y Atsushi Okada por “Yo Soy,” ambos publicados por Akaaka. Esta casa editorial posee un gran respeto en el medio asi como enorme influencia, los cuales son iguales, si no mayores, que los de las galerías de fotografía.

Junto con un pequeño grupo de críticos especializados, los editores de las revistas de fotografía jugaron el papel más importante en la escena de la fotografía japonesa hasta los años ochenta. En los años 90 fueron desplazados por los curadores de museos. Con el siglo XXI llegó el turno de los directores de arte apasionados de la fotografía, tales como Hideki Nakajima o Jun'ichi Tsunoda. Con su capacidad de hallar nuevo talento y libres de cargas institucionales, ellos han podido reunir a su alrededor a la joven generación de fotógrafos.

Una figura destaca entre este grupo de descubridores de nuevo talento: Satoshi Machiguchi quien estuvo detrás del proyecto de “Ikite iru” y desde entonces ha concebido y diseñado una serie entera de libros de arte y fotografía. Para poder trabajar libremente y hacer que algunos de sus sueños se realicen, él concibió una estructura ligera en el 2005 llamada “M Label” Los trabajos que él ha publicado en esta nueva editora se pueden admirar en toda su diversidad en la “Librería M.” Cada uno de estos libros ha sido concebido muy cuidadosamente hasta el detalle más minucioso, y evidencian la relación estrecha entre los fotógrafos individuales y su director artístico. La flexibilidad de Machiguchi le permite realizar sus actividades sin verse atrapado en los circuitos de publicación existentes. El dinamismo de las cinco editoriales presentadas aquí y de los libros producto de sus esfuerzos, ofrecen una comprensión de la esencia de la fotografía japonesa contemporánea y de su evolución actual.

La Sala de Proyecciones en Paris Photo 2008

Desde principios de los 90, un creciente número de fotógrafos japoneses ha comenzado a hacer películas, una tendencia que se puede explicar en parte por el hecho que las distinciones tradicionales entre diversos modos de expresión artística pierden su sentido cada vez más. Este fenómeno claramente se basa en gran parte en el desarrollo de la tecnología digital, la que ha facilitado considerablemente la manipulación de imágenes. Dicho esto, si revisamos la etimología de la palabra, un fotógrafo es alguien que “escribe con la luz”. Naturalmente se deduce que también pueden crear “imágenes en movimiento.”

Hemos montado el programa de la Sala de Proyecciones con el fin de ofrecer al espectador una visión interior que nos permita acercarnos más al trabajo fotográfico de cada uno de los artistas, desarrollado aquí con mayor profundidad o de una manera más experimental. La pieza más antigua aquí presentada es “Shinjuku, 1973, 25 P.M.”, la única película hecha por Daido Moriyama. Fue filmada un año después de la publicación de su legendario libro “Sashin yo sayonara” (Adiós, Fotografía, Adiós), de 1972. ¿Qué resta decir sobre este trabajo, filmado en 8mm, y que fue comisionado por el municipio del distrito de Shinjuku en Tokio, aparte de su carencia total de foco y del hecho de que, de principio a fin, se lee como un vagabundeo sin objetivo a través de las calles en la noche, como el merodear de un perro callejero? No hay puntos de referencia, ni de espacio ni de tiempo, ninguno límite entre lo figurativo y abstracto. La película fue rechazada por las autoridades y olvidada en los estantes por 30 años. Sin embargo, permanece como una reflexión sobre la aproximación radical de Daido Moriyama quien hizo frente a todas las reglas, deconstruyendo imágenes existentes, de la misma forma que en su trabajo fotográfico. Moriyama nunca filmó otra película después de “Shinjuku, 1973, 25 P.M.”

Entre los fotógrafos japoneses que realmente han abordado la cinematografía, Yasumasa Morimura se destaca como pionero. Su primer trabajo en este campo fue “Cometman” (1991), en el cual él se muestra a sí mismo con la cabeza afeitada vagando por las calles de Kyoto y admirando una pintura de Marcel Duchamp, a quien dedicó este vídeo. Él rinde tributo a otro artista, el fundador del “Factory”, en “Yo empuñando un arma: para Andy Warhol.” Morimura es conocido por presentarse disfrazado como figuras escogidas de las grandes obras maestras de la historia del arte. Él sigue esta metodología aquí, no obstante de una manera más teatral.

Tomoko Sawada sigue una aproximación similar, aunque ella se ocupe de temas más íntimos que Morimura, ella también se transforma y es conocida por sus muy coloridas representaciones de los cientos si no es que miles de diversos personajes. En “Máscara” ella juega con la confusión entre la máscara y su propia cara, llevando claramente al espectador hacia la esencia misma de su cuerpo del trabajo.

Otra estrella de la generación joven de fotógrafos japoneses que llegaron a la cima al comienzo del siglo XXI, Rinko Kawauchi, comenzó estudiando cinematografía en la universidad. “Semear” es su primera película desde que alcanzó la prominencia como fotógrafa. El vídeo fue comisionado por el Museo de Arte Moderno de Sao Paulo y se filmó en locaciones en todo Brasil, pero particularmente en las áreas habitadas por las comunidades de origen japonés. La combinación sutil de color, sonido y luz le da a este trabajo la calidad frágil de una burbuja de jabón que contiene el mundo entero.

Mientras que en “Ellos todavía están pegados a tu pared - Versión Gifu”, de Akiko Ikeda ella utiliza un dispositivo al parecer muy simple - aviones diminutos hechos de barro pegados en las ventanas de un tren - para crear una sensación graciosa de un “viajecito” y así explorar la imaginación, tal como ocurre en la vida cotidiana.

Por su misma naturaleza, la fotografía como medio no se limita a ser una manera de producir impresiones de negativos sobre papel fotográfico. Lejos de esto, puede tomar una gran variedad de formas: puede ser impresa en una pagina o ser proyectada sobre una pantalla. Un número de fotógrafos han aprovechado algunas de las características de su medio elegido y han producido películas que no son “imágenes en movimiento”, sino que se componen de una combinación de imágenes fijas. Lieko Shiga es uno de los artistas jóvenes aclamados actualmente en el Japón. Usando sobre todo imágenes que ella no incluyó en su libro “Canario,” (ganador del premio Ihei Kimura en el 2007), ella ha creado un slide-show en el que juega con una alternancia intensa entre la oscuridad y la luz. Mientras tanto, Taisuke Koyama utiliza una cámara digital para producir escenas urbanas de enorme precisión gráfica. Él las ha montado en “Límite X”, un slide-show compuesto de millares de imágenes proyectadas al vertiginoso ritmo de una imagen por décima de segundo. Mucho más allá del placer visual que procuran dar, ambos trabajos tienen la capacidad de proveer al espectador con una experiencia sensorial total muy intensa.

Otros fotógrafos rechazan el mismo principio de la edición y toman el riesgo de abordar otro tema: La continuidad contra la discontinuidad de las imágenes. Osamu Kanemura utiliza una cámara de vídeo para tomar instantáneas en el caos de la ciudad o a lo largo de las calles suburbanas, algo parecido a una hoja del contacto. En “Earth Bop Bound,” él enlaza estos fragmentos al azar en un loop infinito. Este vídeo es indicativo del la aproximación particular de este artista, quien busca las “grietas” que le permitan revelar las discrepancias entre el mundo, la imagen y el hombre.

Finalmente en “Tokyo Bay Ban-Ban”, Ryudai Takano quien es conocido por buscar lo erótico dentro de la vida cotidiana en toda su monotonía, trabaja desde ángulos fijos que parecen haber sido elegidos al azar, emprendiendo un viaje aparentemente sin fin a través de las calles y de los edificios de Tokio en la noche. El espectador eventualmente se percata que el ruido que emana de los huecos oscuros, es de hecho el sonido de los fuegos artificiales en la distancia. Nos guste o no, estas explosiones son recordatorios de los cañones de guerra que están siendo disparados en alguna parte del mundo. En ese sentido, los trabajos de Kanemura y Takano son advertencias silenciosas a nuestra tendencia a considerar las imágenes simplemente como un espectáculo fácil y de novedad.

Mariko Takeuchi

Texto y fotografías cortesía de Paris Photo 2008. Traducido del francés por Philippa Neave.

Mariko Takeuchi, es crítico de fotografía y curadora independiente: Nació en 1972, en Tokio, Mariko Takeuchi ha curado varias exposiciones incluyendo el “Charles FrZ¹ger: Rikishi (Galería de Arte del museo de Yokohama; A.R.T. Tokio, 2005). Ha escrito numerosos textos para catálogos y libros de fotografía incluyendo “Ryudai Takano: 1936-1996” (Sokyu-sha, 2006) y “Ryuichiro Suzuki: Odisea” (Heibonsha, 2007). Ella es colaboradora regular y crítico de fotografía para varias revistas tales como “Asahi Camera” y “Studio Voice”. Ella también se encuentra a cargo de la sección de fotografía japonesa escribiendo para “The Oxford Companionto the Photograph” (Oxford Univ. Press, 2005). Es conferencista de medio tiempo en la Universidad de Waseda, e investigadora invitada del Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno de Tokio.

© 2008 Lens Culture y contribuciones individuales. Todos los derechos reservados.

Top

http://zonezero.com/magazine/articles/takeuchi/indexsp.php

Martes, 04 Noviembre 2008

|

|

Autor:David Pogue

¡Vamos, admítanlo! ¿Hay algo más impresionante que la miniaturización?

El walkman puso un sistema estéreo en su bolsillo y cambió el juego para siempre. Un reloj digital moderno tiene el mismo poder que un cuarto lleno de computadoras en los años 50. Y actualmente la gente está mirando programas de TV en iPods del tamaño de una tarjeta de presentación.

Sin embargo, las hazañas enormes en cuanto a reducciones de estas dimensiones no tienen lugar muy a menudo. Así que cuando ocurren, usted las ve y toma nota –y esto es lo que hará la primera vez que vea el proyector de Optoma Pico (precio de lista $430 dls.). Este proyector desde hace mucho tiempo que se ha estado esperando y muchos rumores han corrido sobre él. Es del tamaño de un teléfono móvil: 2 por 4.1 por 0.7 pulgadas, y pesa 4.2 onzas.

¿Un proyector del bolsillo? ¿Es una broma? Esto no es solo un nuevo producto – se trata de toda una nueva categoría de productos.

Los proyectores regulares, por supuesto, son máquinas grandes, pesadas, costosas, y a veces ruidosas. Son equipo estándar en las salas de reunión corporativas en donde los maestros del PowerPoint ejercen sus habilidades, ya sea en salones de clase, auditorios, o montado en el techo en los home theaters, en donde proporcionan una visión extra grande, con calidad de película.

Pero muchas veces ocurre que una pantalla de 100 pulgadas es demasiado y una pantalla de 2 pulgadas de un iPod no es suficiente. Entonces es cuando se necesita algo intermedio. En esas situaciones que un micro proyector totalmente silencioso, y ridículamente simple como el Pico sale a relucir.

Usted tendría que ser un hastiado adicto a los aparatos electrónicos para no quedar impresionado la primera vez que vea este minúsculo rectángulo negro brillante. En el centro del extremo corto, hay una lámpara muy brillante de luz emitida por un diodo En el interior del proyector hay un chip miniaturizado de procesamiento digital de luz (D.L.P.) de Texas Instruments, en principio similar a los que se utilizan en los sistemas de televisión de alta definición de tamaño normal. Éstos en su conjunto producen una imagen de video asombrosamente brillante, clara y viva. ¡Así es! Esto proviene de un proyector que usted ha sacado del bolsillo de sus jeans.

No hay exageraciones, ni “peros”, ni “vicios ocultos” (como, “no incluye fuente de poder del tamaño de un ladrillo”), porque el Pico se alimenta con una batería. Cada carga dura cerca de 90 minutos – que se alargan si usted utiliza la configuración de brillo más bajo o cuando se reproduce el vídeo sin sonido. Usted puede recargar el proyector ya sea con su cable eléctrico o mediante un cable USB de una computadora. Una batería de repuesto está incluida con el proyector, así como un pequeño bolso para transportarlo.

Un proyector de bolsillo autónomo cambia todas las reglas. Un iPod y un Pico – eso ya es todo el equipo que se necesita. Ahora, por primera vez, la lona de una carpa puede convertirse en una pantalla de proyección si es que usted ha salido a acampar. (Se acabaron aquellos días de hacerse el rudo.)

Pero hay que aclarar: Ningún proyector de bolsillo va a producir tanto brillo como los proyectores normales que son 10 veces más grandes. El Pico maneja 9 lúmenes (medida del brillo utilizada para aparatos), mientras que un proyector estándar de $900 dls. produce 2,000 lúmenes. Suena a que esto es poco, pero es lo adecuado para las distancias más cortas que se manejan con un Pico y los tamaños más pequeños de las “pantallas”.

La distancia mínima para este proyector está a ocho pulgadas de su “pantalla”; el máximo es 8.5 pies de distancia, en cuyo caso se obtiene una imagen de 65 pulgadas. Y si usted reduce la intensidad de las luces o utiliza una pantalla de proyección con una capacidad de reflejo adecuada, obtendrá mejores resultados.

Usted puede acomodar este pequeño aparato en la charola de servicio de un avión y proyectar sobre el asiento frente a usted (¡Sí, lo intenté!.) Usted obtiene una imagen de vídeo asombrosamente brillante, nítida y vívida a una distancia de aproximadamente un pie, para el disfrute de usted y sus compañeros de asiento más cercanos. (O bien, apunte el proyector hacia el techo del avión. La imagen de tres pies desconcertó totalmente a todos los pasajeros en un radio de varias filas; nadie pudo imaginar de dónde provenía, esto también lo intenté y fue muy divertido.)

También usted puede colocar el proyector en un pequeño trípode –se incluye un minúsculo adaptador de tornillo para trípode -- y proyectar el maratón de Wii de esta noche en una sábana o sobre una camiseta.

Usted puede echarse sobre la cama y simplemente apuntar el proyector hacia arriba. En un cuarto a oscuras, usted tendrá una pantalla enorme y brillante en el techo.

No hay manera de realizar un ajuste para poder compensar cuando el proyector se encuentra frente a la pantalla en un ángulo. El bulbo de 20.000 horas de vida, no es reemplazable. Y la resolución de la imagen, es solamente de 480 por 320 píxeles, en el papel es mucho más burda que los 1024 por 768 píxeles (o más alto).

¿Pero saben una cosa? Los píxeles están sobrevaluados. Nadie se quejará por la nitidez de la imagen del Pico, especialmente después de que usted encuentra el punto justo en su pequeña perilla de enfoque. Teniendo en cuenta todo, el Pico se desempeña de una manera sorprendentemente buena.

¿Qué puede usted mirar en esta cosa?

Viene con un cable compuesto especial. En un extremo, hay un minúsculo contacto especial para audio y vídeo que entra al proyector. En el otro extremo, usted encontrará el ya familiar contacto triple tipo RCA con los colores rojo, blanco y amarillo. Éstos son contactos “hembras”, hechos para acoplarse con los cables compuestos “machos” que vienen con prácticamente cualquier reproductor de DVD, VCR, consola de videojuego, cámara digital y videocámaras que se hayan fabricado.

En un santiamén, el proyector Pico podría sustituir un aparato de TV cuando usted esté utilizando aparatos de tamaño regular como los reproductores de DVD o las consolas de videojuego.

Sin embargo, la verdadera misión de la milagrosa miniaturización del Pico es conectarlo a los micro-aparatos de su misma clase: cámaras digitales, teléfonos móviles, iPod o iPhones.

El adaptador necesario para el iPod o el iPhone viene con el proyector. Los viejos iPod de video requieren solamente el cable negro corto, que entra el orificio del auricular del iPod pero éstos son para conectar audio y vídeo simultáneamente. También tiene una pequeña protuberancia de plástico que se encaja a presión sobre la parte inferior del iPhone o de los iPod más recientes; el cable negro corto conecta la protuberancia con el proyector. (El proyector produce una imagen solamente cuando los vídeos se están reproduciendo. No muestra, por ejemplo, el explorador de Internet de los iPhone, el programa de correo electrónico u otras aplicaciones -- una lástima para los instructores o cualquier persona que quisiera demostrar el funcionamiento del iPhone a más de un miembro del público al mismo tiempo.)

Para conectar cámaras digitales, y así mostrar sus fotos fijas o sus vídeos, o conectar su videocámara, se utiliza el cable compuesto de TV incluido en éstas. Optoma planea poner a la venta los cables del adaptador para otros smartphones en los meses entrantes, comenzando con un cable para los Nokia a un precio de $10 USD.

El proyector de Pico hace tantas cosas tan bien y con tan poco, que puede que se oiga quisquilloso el sacar a colación una falla realmente embarazosa. Pero alguien tiene que decirlo: ¿Qué hay del sonido?

El Pico, efectivamente, tiene un altavoz incorporado. Pero es del tamaño de un átomo de hidrógeno. Con el volumen de iPod al máximo, el Pico tiene tanto volumen como el que se escucha de los audífonos de alguien sentado a su lado.

Es decir, el proyector es tan malo con el audio como bueno con el vídeo. Si usted está utilizando un iPod, un iPhone o un teléfono móvil, su mejor esperanza es la conexión de audífonos. Usted puede escuchar a través de audífonos, por supuesto, aunque ésa no sea precisamente una experiencia comunitaria (Un divisor para audífonos le permite invitar a un amigo, por lo menos). O usted puede conectarse a un altavoz portátil -- pero ahora, por supuesto, usted ya requiere de un equipo mucho más complejo y que sale del campo de los artefactos de bolsillo.

Sin embargo, el proyector de Pico es el primero de su clase -- otros micro proyectores llegarán pronto -- y sobre todo, es impresionante. Cuando salga a la venta en dos semanas, proporcionará a los padres un cine totalmente portátil para los niños en el asiento trasero de su mini van. Permitirá a los fotógrafos mostrar sus portafolios con un tamaño e impacto mucho mayores de los que tendría un simple álbum -- directamente de sus cámaras digitales, si es necesario. Permitirá hacer presentaciones espontáneas a empleados corporativos o a cineastas independientes, dondequiera que se encuentren, sin tener hacer complicadas instalaciones o tener que reservar una sala de conferencias.

Miniaturización ¡Es genial!. Hay que querer a esos ingenieros. Solo esperen que pongan sus manos en los acondicionadores de aire, los TiVos y los motores de jet.

David Pogue Noviembre 2008

http://zonezero.com/magazine/articles/projector/indexsp.html

Lunes, 03 Noviembre 2008

|

|

Autor:Vice Magazine

La revista VICE ha colaborado con la iniciativa para la juventud generada por usuarios Ctrl.Alt.Shift, para poner en marcha un proyecto fotográfico único que explora los temas globales del género, el poder y la pobreza. La colaboración creativa toma la forma de una competencia internacional, educando a gente joven en todo el mundo en este importante tema global del desarrollo e invitándoles crear fotografía inspirada por este tema.

El trabajo de los ganadores de la competencia será presentado en las revistas VICE y Ctrl.Alt.Shift, así como en CtrlAltShit.co.uk y exhibido en una galería de Londres junto al trabajo de un embajador de ésta campaña, la legendaria artista fotográfica Nan Goldin de Nueva York - famosa por su colección fotográfica "La Balada de la Dependencia Sexual" - y de un grupo de mentores estrellas del proyecto.

www.ctrlaltshift.co.uk/vice

http://zonezero.com/magazine/articles/vice/indexsp.html

Domingo, 02 Noviembre 2008

|

|

Autor:Pablo Meyer

Descargar PDF

De Pablo Meyer

La idea de este proyecto surgió en 1998, cuando recibí una entusiasta carta de mis primos Roger y Conny Meyer, en la que invitaban a todo el clan Meyer a reunirse y celebrar el cumpleaños de Ilse en Israel, y elaborar un árbol genealógico de los Meyer. Ciertamente esto provocó mi curiosidad, y mientras más averiguaba sobre la familia, más me involucraba en este proyecto. Recuerden que para mí, la definición de una reunión familiar de los Meyer era una visita casual a mi padre –en algún momento, éramos los únicos Meyer en México-.

De repente, resulta que he podido conocer, ya sea en persona o por correo, a la mayor parte de la familia, que posee docenas de miembros vivos.

Martes, 14 Octubre 2008

|

|

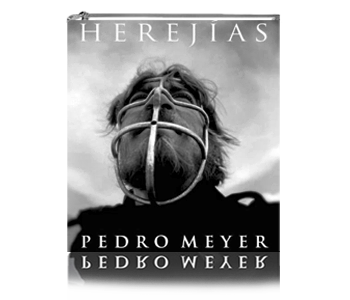

Autor:Pedro Meyer

Descargar PDF

Por Pedro Meyer

Más que una retrospectiva, Herejías es una prospectiva. Su horizonte no es el pasado, sino el porvenir. Tampoco se trata de una simple exposición, sino de un dispositivo: cierto conjunto heterogéneo de discursos, instalaciones, rasgos, hechos y procedimientos materiales y simbólicos que, más que exhibir un corpus, nos confronta con todo aquello que su artífice ha mirado a lo largo de su vida, redistribuyéndolo y convocándonos a observarlo una y otra vez, siempre de nuevo. Pedro Meyer tampoco es un fotógrafo y artista entre otros: es un emprendedor, un polemista y un institutor, cuyas diversas facetas se vigorizan recíprocamente aún más de lo que se contradicen.

¿Cómo abordar aquí a a este creador y su trabajo sin soslayar su amplitud y complejidad?

Lunes, 06 Octubre 2008

|

|

Autor:Benjamin Mayer-Foulkes

Recuerdo ahora mi primera fotografía: un borreguito negro que había nacido de una borrega blanca. En 1947 caminaba por el valle de la Marquesa con mi primera cámara, una Brownie. Observé entonces una oveja que estaba pariendo; no salía de mi asombro al ver que esa oveja blanca daba a luz a un borreguito negro. Preparé mi cámara y disparé hacia esa oscura ovejita que se tambaleaba frente a mí.

Con Herejías, Pedro Meyer deja de ser un fotógrafo de 400 imágenes. Aunque estos pocos centenares de fotografías han brindado un sólido sustento a su prestigio, históricamente ha habido una gran desproporción entre su producción y su obra publicada. Hoy el total de su obra suma más de 300,000 fotografías. El diferencial entre 400 y 300,000 no sólo es inmenso, es enigmático. “¿Para qué habré tomado tantas fotografías, si ni siquiera las exhibía?”, se pregunta Pedro.

“Soy un hombre-cámara”, resume. Desde temprana edad la fotografía ha sido una presencia permanente en su vida: “En ciertos momentos de aguda pena personal, captar imágenes era para mí la única posibilidad de tratar de comprender más adelante lo que pasaba". La fotografía ha sido el mayor de los órganos del cuerpo imaginario de Pedro Meyer, su piel misma: la fotografía le ha brindado estructura a su persona, lo ha protegido, ha posibilitado sus percepciones, ha promovido su contacto con los otros y ha facilitado sus capacidades de articulación. Pero, además, dicha epidermis subjetiva ha sido resguardada, regenerada, reforzada, extendida y ensanchada por una potentísima prótesis: la digitalidad.

Meyer fue el comprador de la primera Apple vendida en México. Al encenderla se produjo un parteaguas en su vida; las implicaciones de la informática le parecieron inmediatamente obvias y deseables. Sabemos de los muchos años que ha pasado abogando a favor de la fotografía digital, batiéndose con otros; pero la virulencia de la pugna sólo se entiende al tomar en cuenta su trasfondo religioso. Pues la digitalidad es mucho más que un nuevo modo tecnológico: el paso de lo analógico a lo digital es el correlato de la ruptura radical de cierto orden teísta. El desplazamiento de la jerarquía por la red, la sustitución de la transmisión unidireccional por la interactividad, y el paso de la unicidad a la multiplicidad suponen —en conjunto— dejar atrás aquella teo-lógica según la cual un punto central, de sí mismo absoluto, da lugar a una serie de términos derivados, más y más infieles a su origen.

En el caso de Herejías, la interfase digital permitió a Pedro franquear las oposiciones tradicionales entre lo privado y lo público, lo abarcable y lo inabarcable, para hacer emerger —a partir de la invitación a montar una exposición retrospectiva en el Centro de la Imagen— esa formidable epidermis procurada por él durante tantas décadas, más por una pulsión íntima —cuya última capacidad es deicida— que por un afán de comunicar. Oportunidad determinante, ésta, para que ese aparato fotográfico, antes omnipresente en su vida familiar y personal, se transfigurara en un dispositivo cuyo alcance lo hiciera extensible a una colectividad indeterminada de sujetos sin una espacialidad o temporalidad precisas.

Por eso, Herejías no es el ordenamiento final de una larga trayectoria creadora; su tiempo no es el de una historia que revelaría una verdad pasada, sino el de la promesa de un entendimiento siempre por venir. Observar sus imágenes es invocar la posterioridad de una comprensión de la que carecemos en el presente. De ese modo, Herejías lleva a cabo con la retrospectiva lo que ya se ha producido en nuestra actualidad crítica con el autorretrato y la autobiografía, géneros que no hacen sino destruir aquello mismo que fingen representar: así como el sujeto es en verdad el residuo dejado atrás por las operaciones del retrato y de la escritura del yo, así también la sustancia activa de Herejías es aquello mismo desechado por la retórica del gesto retrospectivo —la prospectiva de una obra y de una vida siempre en ciernes.

De entre todos los relatos que le he escuchado a Pedro, ninguno me ha parecido condensar tan llana y precisamente el ánimo común a su persona y a su producción que el recuerdo de su primera imagen, hoy extraviada (y por consiguiente aún no incorporada a Herejías). El primer retrato de Pedro, en cuya producción posterior tanto abundan los retratos como los autorretratos, puede considerarse asimismo como su primer autorretrato.

Pedro dice siempre haberse sentido como un outsider. Cuando asistía a la escuela con los maristas, entre setecientos estudiantes era uno de sólo cinco niños judíos: tenía que presentarse al catecismo, adonde llevaba sus propias lecturas; su primer libro elegido, Los tres mosqueteros, estaba prohibido. Cuando en otro tiempo fue enviado a una academia militar en Estados Unidos, se negó a marchar con un rifle por parecerle “una completa estupidez”: todos sus compañeros cadetes se graduaron como oficiales, él fue el único que egresó como soldado raso. A los trece o catorce años, Gerhard Herzog, un querido amigo de su padre, le regaló un equipo fotográfico con el que produjo sus primeras tiras de contactos; cuando a los treinta y ocho años anunció que había decidido dedicarse profesionalmente a esa actividad, don Ernesto Meyer se opuso y sufrió un intenso vértigo; pretendía que su hijo se dedicara a algo más serio que le asegurara un buen sustento a su familia: fue Gerhard quien persuadió a su camarada de que la cosa no era tan grave.

Mas Pedro no sólo discrepa. A la vez que se identifica con esa oveja negra, lleva a cabo el fotograma. Como en cada una de esas cientos de miles de ocasiones posteriores, en esa primera oportunidad su mirada tras la lente (situada en el perímetro exterior de la bucólica maternidad) se ubica en el mismo punto donde siempre estuvo su padre, ora exiliado, ora viajero. Rizoma de esa luminosa película epidérmica que de ahí en más arropará a la persona de Pedro, en presencia y en ausencia de su papá, como también más allá de él, y cuyos alcances personales y profesionales serán cada vez mayores hasta llegar a la escala insólita de proyectos como ZoneZero y Herejías, capaces de corroer los cimientos mismos del status quo fotográfico de su tiempo. Diáfana piel que Pedro siempre habrá insistido en compartir con otros mediante el impulso y la promoción de la fotografía, de los fotógrafos y del fotografiar, no meramente como una técnica, un arte o un recurso social, económico o político, sino como una apuesta existencial. Con la mediación de la lente y la pantalla, la oveja negra ha transmutado en el mago que hoy preside ese horizonte abierto que es www.pedromeyer.com.

NOTA: El presente texto condensa algunas de las ideas vertidas por mí en “Negro. Oveja. Mago.”, ensayo introductorio del volumen Herejías (Lunwerg, Barcelona, 2008) que forma parte del proyecto Herejías.

Benjamin Mayer-Foulkes bmayer@17.edu.mx

Septiembre 2008

**

Benjamín Mayer-Foulkes Psicoanalista, investigador y gestor cultural. Fundador de 17, Instituto de Estudios Críticos (www.17.edu.mx). Maestro en Teoría Crítica por la Universidad de Sussex, Doctor en Filosofía por la UNAM. Sus trabajos sobre psicoanálisis, filosofía, historia y arte han sido publicados en español, inglés, italiano, francés y portugués. En el ámbito fotográfico es reconocido como uno de los exponentes internacionales del debate sobre la fotografía realizada por ciegos.

Como siempre, por favor pongan sus comentarios en nuestros foros.

http://zonezero.com/editorial/septiembre08/septiembre08.html

Martes, 02 Septiembre 2008

|

|

|

Autor:Alison Watt Jackson

Date: August 26, 2008 10:09:04 PM

I am sending this email to compliment on your amazing photographic publication and web site. Not only are ZoneZero's gallery photos original, intruiging and first rate, but the bylines and the presentation of your entire web site is next to none. It is a thorough pleasure to visit your site!

I would be honored to have you register me with ZoneZero. Thanks much.

~Alison Watt Jackson

Martes, 26 Agosto 2008

|

|

Autor:Rogelio Villarreal

Hace cincuenta años, cuando nací, era inconcebible aun en las más fantásticas películas de ciencia ficción lo que viviríamos al fenecer el siglo XX y al alba de éste. No el cómodo y divertido futuro de Los Supersónicos (The Jetsons) ni el catastrófico mundo de El planeta de los simios (Planet of the Apes, Franklin J. Schaffner, 1968), pero sí uno más apasionante y complejo, más cerca del angelino 2019 de Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982) y, por desgracia, a veces de la desesperación neoyorquina de Cuando el destino nos alcance (Soylent Green, Richard Fleischer, 1973).

En nuestros días los apabullantes adelantos tecnocientíficos en todos los ámbitos de la vida son comunes a las novísimas generaciones —desde luego, a las que por distintas circunstancias tienen mayor acceso a ellos: millones de niños y jóvenes de hoy en todo el mundo no podrían concebir sus actividades cotidianas sin iPods o teléfonos celulares con cámaras fotográficas y GPS integrados, sin chats, redes sociales y juegos en línea cada vez más sofisticados. Y seguramente no disfrutarían de la misma manera una película sin espectaculares efectos digitales y otra filmada sin tantos artificios. Y qué decir de la radical transformación de la educación, del arte, del periodismo y de la investigación en general debida a la inagotable hiperbiblioteca virtual que envuelve al mundo y que sorprendería al mismísimo Borges, quien ya aventuraba mucho de esto en su Aleph. La llegada del hombre a la Luna en 1969 y el descubrimiento del genoma humano hace unos años —por hablar solamente de dos momentos culminantes de la ciencia— habrían sido imposibles sin la tecnología digital.

En la casa de mis padres no hubo televisión —en blanco y negro— sino hasta mediados de los años sesenta, y teléfono —¡qué maravilla!— unos años después. Las amarillentas fotografías de la familia y los amigos eran resguardadas en gruesos álbumes de hojas de cartón negro y mis primeras tareas escolares al final de la escuela primaria las escribía en una moderna máquina mecánica de escribir Olivetti, y debía recurrir una y otra vez a la biblioteca de mi padre para consultar fechas y nombres históricos.

Ya que lo menciono, mi padre trabajó sucesivamente como linotipista, corrector y editor. ¿Linotipista? Les explico: el linotipo es una enorme máquina de escribir con un caldero lleno de plomo fundido que servía para componer las líneas tipográficas que formarían las planas de libros, revistas y diarios. Hoy es una pieza de museo, como el que se encuentra en el edificio del Fondo de Cultura Económica en la Ciudad de México, a las faldas del Ajusco. Actualmente los talleres de imprenta tienen máquinas de offset silenciosas, del tamaño de un tráiler, operadas por computadora. Para diseñar una publicación es suficiente con una laptop y un par de programas de edición. Muy lejos en el pasado quedaron los restiradores, el cutter, el laborioso paste-up y las aparatosas máquinas de fotocomposición, que recuerdan a esos armatostes plagados de foquitos de los científicos deschavetados en las candorosas películas del Santo, el Enmascarado de Plata. En estos días ya no es necesario llevar los originales mecánicos a la imprenta, pues éstos pueden enviarse rápidamente por correo electrónico, aun si la casa editora se encuentra en Honk Kong o en Shanghai.

Hace más de veinte años Pedro Meyer me hizo un retrato digital, el primero en mi biografía. No se distinguía por su calidad pues se trataba de una gran imagen compuesta de grandes puntos negros que solamente observada desde varios metros podía hacer reconocible mi rostro. La distancia entre esa fotografía y las que Meyer ha creado últimamente con una técnica digital sumamente depurada hasta la perfección es abismal. Todos los que han visto las imágenes digitales de Pedro saben de la revolución conceptual que significa poder componer fotografías perfectas a partir de dos o más tomas diferentes captadas en distintos momentos y lugares.

Todo aquello que sucedió antes de la era digital es prehistoria para los niños y los adolescentes que han crecido y han sido educados en un entorno de nuevas tecnologías digitales, y que entre ellas se mueven como peces en el agua. La semejanza entre el pensamiento y el funcionamiento de las computadoras y el internet ha facilitado en mucho esta identificación natural. Los vínculos y el hipertexto son el reflejo casi exacto de la manera en que funciona el cerebro humano y su pensamiento no lineal, que procesa simultáneamente imágenes y conceptos y brinca de un tema a otro, avanza o retrocede en el tiempo y en el espacio intencionalmente o por libre asociación, de modo muy semejante a como aparecen los resultados de una búsqueda en internet.

La tecnología digital también se utiliza para el espionaje, la destrucción y la guerra, y en ese sentido el mundo no es mejor que antes. Hay Estados cuyo desprecio por la democracia los ha llevado a prohibir el uso de internet a la población e incluso a vigilarla y hostigarla por este medio, como lo hizo el gobierno chino con los blogs de los escritores disidentes Tsering Woeser y Wang Lixiong por los comentarios de éstos en favor de la independencia del Tíbet. “La pareja se encuentra bajo arresto domiciliario desde el inicio de los disturbios, el pasado 10 de marzo”, escribe la escritora mexicana Eve Gil, y continúa:

La censura en internet se ha extendido a los mensajes SMS con la colaboración —¿complicidad?—, ¡claro!, de empresas como Yahoo y Google. China cuenta con el sistema de filtro y censura con mejor tecnología y de mayor alcance del mundo, y gracias a esto ha llevado a la cárcel a por lo menos medio centenar de usuarios [“China reinventada”, Replicante magazine, issue 16.]

Otro ejemplo de rampante desprecio a la libertad de expresión de los ciudadanos tiene lugar en Cuba, en donde un mínimo porcentaje de la población tiene computadora y acceso a internet. En un informe de la organización Reporteros Sin Fronteras puede leerse que:

A pesar de que es verdad que en Cuba existen dificultades para establecer conexión con Internet, resulta muy difícil creer que www.desdecuba.com lleve diez años enfrentándose con simples problemas técnicos. Este tipo de restricción va en contra de las recientes medidas adoptadas por las autoridades para facilitar el acceso de los cubanos a los medios de comunicación, y entre ellos a la Red. Porque una cosa no puede existir sin la otra. Las muestras de apertura que ha dado Raúl Castro deben incluir mayor libertad de expresión.

Y añade que:

Desde el 20 de marzo de 2008 no se puede acceder a la plataforma www.desdecuba.com a partir de conexiones públicas, disponibles en los cibercafés y en los hoteles. Las escasas conexiones privadas, utilizadas por motivos profesionales o de forma clandestina, tardan al menos veinte minutos en cargar la página de entrada. Resulta imposible hacer comentarios, y también moderarlo.1

La red de internet en Cuba está controlada férreamente por el Estado. Hay una única red que da acceso a una dirección electrónica y permite enviar correos electrónicos fuera del país, pero no navegar por internet, de acuerdo con el informe de Reporteros Sin Fronteras.

La conexión a la red internacional, que es tres veces más cara, permite acceder a sitios informativos extranjeros, como los de la BBC, Le Monde o el Nuevo Herald (diario en español de Miami). Pero si se escribe “google.fr” le dirigen a uno a las páginas del periódico oficial de Cuba (Granma) o a las de la agencia Prensa Latina.

No es de extrañar que Cuba figure en la lista de Enemigos de Internet publicada por Reporteros sin Fronteras el 12 de marzo de 2008.

Uno de los blogs más populares de Cuba, y ahora del mundo pues ha merecido el Premio Ortega y Gasset 2008 de Periodismo Digital, es Generacion Y. de Yoani Sánchez, en el que esta joven comenta de manera sencilla cuestiones de la vida cotidiana en la isla de Castro ilustradas con tristes fotografías de edificios derruidos, policías en busca de homosexuales, medidores de luz destartalados y las alegrías eventuales del carnaval. Paradójicamente, Yoani no tiene computadora en casa...

Así, la tecnología digital y sus ventajas no son para todo el mundo, a pesar de su vertiginoso crecimiento. En este sentido, es lamentable que millones de chinos y cubanos carezcan de acceso total e irrestricto a la red de información, educación y entretenimiento más importante y decisiva en la historia de la humanidad, pero también lo es que se vean privadas de ella millones de personas en África y America Latina que habitan en países democráticos —o en camino de serlo— debido a la pobreza, el desempleo y a la ausencia de políticas educativas y de desarrollo científico y tecnológico avanzadas. La tecnología digital puede cambiar positivamente al mundo, pero ésta sólo puede florecer en un ambiente de libertad, respeto y prosperidad económica. Ya hemos vivido suficientes guerras. Si los medios son las extensiones del hombre, como decía McLuhan, en el siglo digital las nuevas tecnologías deben estar al servicio del crecimiento y el desarrollo pacífico de mujeres y hombres de todo el planeta.

__

1. www.cubanet.org/CNews/y08/abril08/01inter6.html (back)

Rogelio Villarreal rogelio56@gmail.com

Agosto, 2008

**

Rogelio Villarreal es autor de El dilema de Bukowski (Ediciones Sin Nombre, 2004) y de El periodismo cultural en los tiempos de la globalifobia (Conaculta-Ediciones Sin Nombre, 2006); es escritor y editor de la revista Replicante.

Como siempre, por favor pongan sus comentarios en nuestros foros.

http://www.zonezero.com/editorial/agosto08/agosto08.html

Sábado, 02 Agosto 2008

|

|

Autor:Fernando Castro

Leí recientemente una crítica extremadamente negativa de la exposición "Juan Alexander: Una retrospectiva", que tuvo lugar en el Museo de Bellas Artes de Houston. El acre tono de la reseña me recordó por qué es que yo no escribo críticas negativas. El crítico se lanza no sólo contra la obra, sino también contra el artista mismo: “la estrategia de Alexander de dar grandes brochazos expresivos funciona bien para ocultar sus defectos artísticos" y "Caramba, este individuo realmente es un mal pintor”.1 En toda mi vida, caí solamente una vez en la trampa de escribir una crítica negativa. No solamente me resultó una tarea extremadamente difícil el demostrar por qué una fotografía bien ejecutada era superficial, sino en última instancia también sentí que había sido un esfuerzo infructuoso.

Supongo que los críticos de teatro, cine o culinarios que señalan las fallas de los actores que no actúan bien sus papeles, las historias que no convencen a nadie, o los mariscos demasiado cocidos, realizan un valioso servicio público al calificar obras de teatro, películas y restaurantes con cero a cinco estrellas. Después de todo, la gente no desea perder su dinero ganado con tanto esfuerzo para ver una producción pobre o comer una paella poco apetitosa. Pero en la fotografía, la pintura y otras artes visuales por el estilo, el público raramente tiene que pagar para verlas y se puede marchar de una galería siempre que lo desee. Si bien es verdad que en muchos museos la gente tiene que pagar, una vez que una obra de arte ha llegado allí, ha pasado a través de suficientes filtros como para hacer de la elección una mera cuestión de gusto. En resumen, no veo a la crítica de arte como un servicio de calificación que requiera que el crítico de arte escriba críticas negativas. Para mí la crítica del arte no se trata de alabar o condenar, sino de interpretar.

El argumento de que “no es un servicio de calificación" es solamente una razón por la que no escribo críticas negativas. He aquí algunas otras. Primero, me equivoco más a menudo de lo que quisiera. Así que podría causar un serio daño si fuera a condenar una obra como la de Vincent Van Gogh, por ejemplo. Muchos artistas importantes tuvieron y tienen detractores: Murillo, Gauguin, Vasarely, Dalí Frida Kahlo, Chagall, Paul Jenkins, Andrew Wyeth, etc. Los que tenemos el poder de publicar debemos ejercitarlo con prudencia, modestia y discreción. Si una obra de arte me pareciera "carecer de méritos", permitiría que alguien más inteligente que yo me convenciera de lo contrario; o, si nunca me convenzo de sus méritos, simplemente la dejo pasar en cortés silencio. De hecho, el silencio es a menudo el comentario negativo más devastador - ¡Ni siquiera se puede buscar en Google!

En segundo lugar, aunque se requiere que un filósofo sea un tanto iconoclasta, parece una pérdida de tiempo y energía ensañarse contra las obras de arte y los artistas —a menos que los asuntos en juego vayan más allá del arte—. El entusiasmo corrosivo, en general es mejor dirigirlo hacia temas políticos, económicos, sociales, ambientales y morales de mayor importancia. Los artistas deberían de poder tomar riesgos sin temer incurrir en equivocaciones y un crítico debería no solamente permitir que exista esa libertad, sino ayudar también a generarla. Por cierto, a veces uno está tentado a romper el cortés silencio cuando se celebran las obras y los artistas mediocres. Sin embargo, tal situación es más una prueba para un crítico que para las instituciones del arte. ¿Después de todo, quién va a ser engañado? Vive y deja vivir, digo yo. Si alguien puede ganarse una buena vida vendiendo arte cuestionable, tanto mejor para ellos. A largo plazo, esto es bueno por una variedad de razones: su efecto multiplicador en la economía, el dinero está mejor gastado en mal arte que en coches que contaminan, los ricos que están más felices a pesar de su caro y mal gusto podrían contribuir generosamente a proyectos de arte, etc.

En tercer lugar, al estudiar el movimiento de arte indigenista, llegué a la conclusión de que algunas pinturas "mediocres" son realmente importantes y dignas de reflexión. Es un error pensar que los valores del arte están totalmente aparte de los de la sociedad en general, aunque no sean exactamente iguales, hay de hecho traslapes significativos. Los pintores indigenistas trataron temas que, debido a una variedad de razones racistas e ideológicas, fueron considerados por muchos como indignos de ser representados; a saber, los pueblos y las culturas indígenas. De hecho, en el apogeo de la pintura indigenista, un crítico antagónico calificó a su trabajo como "pintura de lo feo”, un ataque más dirigido al tema de ese arte que al arte mismo o al artista, y que ahora, bochornosamente es más revelador de sus propios prejuicios.

La crítica negativa hacia John Alexander también me recordó una de las primeras lecciones que aprendí sobre lógica y filosofía: evitar prudentemente comentarios ad hominem y tratar siempre las tesis (las obras de arte), nunca la persona que las propone (el artista). Por otra parte, aun cuando sólo discuto las obras, contengo mi entusiasmo y evito los elogios. La descripción laboral de un crítico de artes visuales no debe incluir el elogiar, ni condenar sino sólo informar, conectar, contextualizar, explicar, clarificar y proporcionar interpretaciones plausibles de los trabajos. Por último, existe una distinción importante entre un tema difícil y un lenguaje oscuro. Tanto los escritores como los lectores deben aceptar el desafío de temas complejos, mas no tienen que ser alienados por un lenguaje oscuro ni por teorías innecesarias. El arte, como el Jazz, es para todos, aunque solamente algunos decidan desarrollar un gusto por él.

Una vez un profesor francés me preguntó qué método de crítica practicaba en mi escritura crítica. Por un microsegundo sentí que quizá había estado jugando al tenis sin raqueta, pero un nanosegundo después, recordé que era filósofo. Para interpretar obras de arte empleo cualquier medio racional usado por Sherlock Holmes para solucionar un crimen, desde el pensamiento inductivo cuidadoso y la conjetura calculada, hasta la lógica deductiva y la probabilidad. Uno tiene que preguntarse: quién es la víctima, cuál es la evidencia, dónde fue perpetrado el crimen, cuáles fueron las motivaciones posibles de los autores, quiénes son los posibles culpables, cuánto importa el crimen, quién se beneficia con él, qué responsabilidad tiene la sociedad, etc. Aunque me incomoda la idea de seguir métodos, llamé a esta manera de pensar sobre el arte "psicoanálisis ideológico", porque intenta entender las ideas detrás de una obra y de la mente que la produjo. Así que es ideológica sin ser marxista y psicoanalítica sin ser freudiana. Mientras más misterioso y atroz es un crimen, mayor es la exigencia hacia nuestro pensamiento. Sin embargo, si el crimen es un robo de poca monta no se necesita involucrar a Sherlock Holmes.

__

1. Para consultar la mencionada crítica negativa, visitar: http://houstonpress.net/2008-06-05/culture/john-alexander-the-mediocre/ (back)

Fernando Castro R. eusebio9@earthlink.net

Junio 2008

**

Fernando Castro R. estudió filosofía en Rice University como becario Fulbright (1979-1985). Su libro Cinco Rollos de Plus-X (1982) alterna fotografía y poesía. Su carrera de crítico comenzó en 1988 escribiendo para El Comercio (Lima). Desde entonces ha colaborado con Lima Times, Photometro (San Francisco), Art-Nexus (Colombia), Cámara Extra (Caracas), ZoneZero.com (México), Artlies, Visible, Literal, Spot (Houston), Arte Al Día (Miami), Aperture (New York), etc. Su trabajo curatorial incluye "La Modernidad en el Sur Andino: Fotografía Peruana 1900-1930"; "El Arte del Riesgo / El Riesgo del Arte" (1999), “Piedra” (2004), “El Arte de la Guerra” (2006) y "Con Otros Ojos" (2007). Su propia obra fotográfica tomó un giro político en 1997 bajo el título "Razones de Estado". Su muestra individual más reciente “La Ideología del Color” (2004) en el Centro Cultural Borges de Buenos Aires es ahora una exhibición virtual en el website de la Universidad de Lehigh. Sus obras forman parte de las colecciones permanentes del Houston Museum of Fine Arts, The Dancing Bear Collection (New York), Lehigh University (Pennsylvania), Museo de Arte de Lima, Harry Ransom Research Center (Austin), etc. Actualmente reside y trabaja en Houston.

Como siempre, por favor pongan sus comentarios en nuestros foros.

http://www.zonezero.com/editorial/junio08/junio08.html

Lunes, 02 Junio 2008

|

|

Autor:Irene Méndez and Mariana Espinoza

Nos da mucho gusto el poder presentar este libro, que muestra práctica y sencillamente la forma de utilizar las imágenes y su poder de comunicación visual dentro de su empresa y en la vida cotidiana. Going Visual, es una oportuna publicación donde uno puede encontrar información acerca de la tecnología, la fotografía y la comunicación, en torno a las necesidades de una pequeña, mediana y grande empresa, como las de aumentar la productividad, los beneficios y acelerar la toma de decisiones.

La idea principal citando a Philippe Kahn y retomada por los autores es la de una imagen tiene el valor de mil palabras, una imagen con texto vale diez mil palabras, y si a esto se le agrega sonido, tiene un valor de un millón de palabras. La fotografía digital ha acelerado el proceso de creación de una imagen, reduciendo los tiempos de creación y los conocimientos necesarios para crearla. Las cámaras digitales, los teléfonos con cámara integrada y el internet, pueden transportar una imagen a cualquier rincón del mundo abarcando así a un extenso público.

Going Visual nos explican ampliamente cuales son los requerimientos necesarios para cualquier persona o empresa que desea introducirse en el mundo de la fotografía digital y su aplicación práctica. Así como la estrategia de los cinco pasos a seguir para planear e implementar la nueva tecnología digital.

El libro es muy bueno, en la manera que nos invita a realizar varios ejercicios como el ir de compras y tomar una foto de lo deseado, ropa, muebles, etc., enseñarla a la familia, la pareja, la amiga, etc., y así poder tomar una decisión más rápida de si va ser, o no, una buena adquisición.

También nos muestra varios ejemplos. Sally Carrcino, una vendedora independiente de accesorios para el hogar y jardinería, nos comparte su experiencia. Ella ha hecho catálogos en línea de sus productos como lámparas, plantas, etc., para que las personas puedan verlos por internet y si lo desean hacer sus pedidos. Otro ejemplo es el de una inmobiliaria que ha reducido en espacio los inventarios que antes se hacían de forma escrita, logrando una mejor descripción de las casas a través de fotos. Estas pueden ser consultadas por internet antes de ir a ver la casa físicamente, ahorrando así tiempo tanto de la inmobiliaria como del cliente. En el mantenimiento de una máquina o una fábrica la fotografía ha logrado reducir los tiempos para arreglar un problema. Esta puede ser consultada por varios expertos, sin la necesidad de la presencia física, o a través del análisis de las mismas para ubicar fallas que pudieran ocasionar un futuro problema.

Es importante hacer archivos en donde se clasifican las imágenes. Going Visual propone diversas formas ya sea en catálogos, inventarios, por temáticas, etc., para poder compartir la información, con las personas que se requiera.

Al final del libro se analizan las nuevas propuestas tecnológicas como lo es la tele-conferencia. En una universidad, empresa o situación familiar, donde las personas se encuentren en otro lugar lejano, a través de una pantalla pueden compartir un espacio virtual, logrando reducir el sentimiento de lejanía. Gente de diversas partes del mundo pueden tomar decisiones, en su lugar y momento, sin tener que estar físicamente en el mismo espacio.

Alexis Gerard, fundador de Future Image, en donde se realiza la investigación acerca de la convergencia de imágenes, información tecnológica y negocios; y Bob Goldstein fundador de ZZYZX Visual Systems, donde se manejan grandes volúmenes de tecnología visual para empresas, presidente del Grupo Altamira, dedicado a producir software para imágenes digitales, y asesor corporativo en comunicación visual, nos presentan aquí con toda su experiencia las últimas novedades en comunicación visual.